Vaccine-induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia: pathogenetic and epidemiological issues of concern

Posted: 5 May 2021 | Giovanni Di Guardo DVM Dipl. ECVP | No comments yet

Giovanni Di Guardo, DVM, Dipl. ECVP, retired Veterinary Pathologist, discusses the association between adenoviral vector COVID-19 vaccines and rare blood clots, outlining four areas warranting further research.

Since recognising the existence of a likely cause-effect relationship between the administration of AstraZeneca’s and Janssen’s COVID-19 vaccines and vaccine-induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia (VIPIT), an extremely rare blood clotting disorder, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has officially re-admitted the two adenoviral vector-based vaccines for use throughout the European Union. The two decisions recently adopted by EMA were substantially based upon the undeniable fact that the benefits provided by the mass immunisation against COVID-19 with the vaccines fare outweigh the VIPIT-associated or related risks.

Indeed, while SARS-CoV-2 – the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19 – has already caused almost 145 million infection cases and over three million deaths worldwide, with several dangerous SARS-CoV-2 “variants of concern” having also been identified,1 VIPIT has been reported in approximately one out of 150 thousand vaccinated individuals, mostly females less than 50 years-old, with a fatal outcome involving one out of 1.0-1.5 million immunised people. We are undoubtably dealing, therefore, with a vaccine administration-related blood clotting disorder which deserves a lot of concern and attention, but we are talking about, most importantly, an extremely rare adverse reaction (since “zero risk” does not exist anywhere) which should not compromise, in any way, our faith in vaccination.

Thanks to mass vaccinations, in fact, smallpox was totally eradicated from our planet in 1980, with polio, another devastating viral disease, being also very close to global eradication nowadays. The same holds true for viruses impacting animal, as in the case of Rinderpest morbillivirus, which causes rinderpest in cattle, and was officially eradicated from Earth in 2011, thanks to the mass vaccinations.

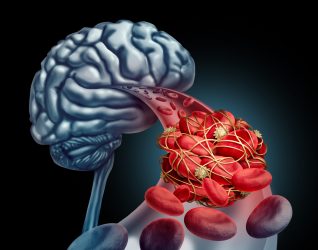

Patients affected with VIPIT showed brain venous (cavernous sinus) thrombosis (CVST) or, less commonly, splanchnic vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and other thromboses, with VIPIT having been pathogenetically linked to an autoimmune disorder.2 Indeed, autoantibodies against platelet factor 4 (PF4)-heparin, a self-antigen expressed on the surface of platelets (thrombocytes), were demonstrated in the blood serum from these individuals, with their coagulation disorder clinically resembling autoimmune heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (AHIT).2

Within such context, I believe there are several key pathogenetic and epidemiological questions deserving of consideration:

Why is VIPIT apparently more common in females than in males and what may be the role, if any, of female sex hormones (estrogens)?

This would be of interest also in consideration of the role played by male sex hormones (androgens) in modulating SARS-CoV-2 infection’s susceptibility, with male patients being much more prone than females to develop particularly severe COVID-19 disease forms.3

Why is VIPIT reported more frequently in patients (mostly females) less than 50 years-old?

Indeed, under natural disease conditions, the most consistent COVID-19-related/associated intensive care unit hospitalisation and mortality rates are found among elderly subjects, with special emphasis on those affected by pre-existing comorbidities.3

Since both AstraZeneca’s and Janssen’s COVID-19 vaccines are adenoviral vector-based, how does the frequency rate of VIPIT following large-scale immunisation with Sputnik V, the Russian vaccine candidate using the same technology, compare?

All of these adenoviral vector-based vaccines induce an immune response against the SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) protein, the major surface antigen which allows the virus to bind to and enter human host cells expressing the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor. While AstraZeneca’s Vaxzevria uses the same adenovirus in both doses received by each patient, Janssen’s vaccine is a single dose regimen and Sputnik V employs two different adenoviruses in its two doses.

3D illustration of the structure of an adenovirus, the type of virus used as a vector in several COVID-19 vaccines

This could help decipher if the adenoviral vector may play a role. Furthermore, when using any viral vector in vaccines, we should remember that the injected hosts’ immune reaction will preliminarily target the vector carrying the genomic information needed for host cells to temporarily produce the genome and thus induce an immune response, namely SARS-CoV-2 S protein. The reason behind this has nothing to do with the pathogenicity, if any, possessed by the viral vector but simply that our immune system defending us from something it perceives as foreign, or expressing ‘non-self’ antigens. Therefore, should any viral or non-viral agent not previously encountered by us enter our body, our immune system will mount a response against it, independently from it being or not being pathogenic – as in the case of the adenoviral vectors employed for COVID-19 vaccine production, which are totally harmless to humans.

As both severe COVID-19 pathologies and COVID-19 vaccine adverse reactions are autoimmune related, does the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 S protein play a common pathogenic role in both?

The most severe cases of COVID-19, leading to a fatal outcome in approximately two percent of infected patients, are pathogenetically linked to an autoimmune reaction targeting platelets and other factors, including Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), multi-organ inflammation and dysfunction, cytokine storm and DIC.3 Within the complex framework of SARS-CoV-2-host pathogenetic interactions, there have also been reports of blood clotting disorders similar to those in VIPIT-affected humans, with their occurrence justifying the question of a common pathogenetic role exerted by the host’s immune response to SARS-CoV-2 S antigen. This could be alternate, if not complementary, to the previous question concerning the adenoviral vaccine vectors. To this end, it would be of interest to investigate whether these autoimmune reactions, both in COVID-19-affected patients and in subjects vaccinated with the COVID-19 vaccines, tend to preferentially occur in Th1-dominant versus Th2-dominant individuals.

Conclusion

These questions are undoubtedly a lot of food for thought and will require a lot of challenging but urgently needed research work to answer. Additionally, of course, they are also not the only key questions on the table. However, it is most important to note that there is a firm and objective conclusion: whatever the vaccine we have been, are being, or will be administered with, the benefits of getting immunised against COVID-19 are enormously greater than the vaccination-associated or related risk, which should be regarded as almost negligible from the statistical viewpoint. Do not forget that SARS-CoV-2 has already caused almost 145 million infection cases and over three million deaths worldwide and that zero risk does not exist!

About the author

Giovanni Di Guardo, DVM, Dipl. ECVP, is a retired Veterinary Pathologist and Past-Professor of General Pathology and Veterinary Pathophysiology at the Veterinary Medical Faculty of the University of Teramo, Italy.

References

- Lauring A, Hodcroft E. Genetic Variants of SARS-CoV-2—What Do They Mean?. JAMA [Internet]. 2021;325(6):529-531. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2775006

- Greinacher A, Thiele T, Warkentin T, Weisser K, Kyrle P, Eichinger S. Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCov-19 Vaccination. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2021;. Available from: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2104840

- Albini A, Di Guardo G, Noonan D, Lombardo M. The SARS-CoV-2 receptor, ACE-2, is expressed on many different cell types: implications for ACE-inhibitor- and angiotensin II receptor blocker-based cardiovascular therapies. Internal and Emergency Medicine [Internet]. 2020;15(5):759-766. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11739-020-02364-6

Related topics

Biologics, Drug Safety, Immunisation, Research & Development (R&D), Vaccine Technology, Vaccines, Viruses

Related organisations

Related drugs

COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca, COVID-19 Vaccine Janssen, Sputnik V, Vaxzevria (COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca)

Related diseases & conditions

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), Coronavirus, Covid-19, Cytokine storm, thrombosis, Vaccine-induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia (VIPIT)