FMD alerts in 2020 – where we are a year into legislation

Posted: 13 July 2020 | Grant Courtney (Be4ward) | No comments yet

Over a year since the EU FMD came into force, false alerts remain a problem preventing the realisation of the full benefits of the directive. Grant Courtney examines the reasons behind these alerts occurring and looks at the action stakeholders must now take.

Over a year since the EU FMD came into force, false alerts remain a problem preventing the realisation of the full benefits of the directive. Grant Courtney examines the reasons behind these alerts occurring and looks at the action stakeholders must now take.

On 9 February 2019, new legislation was introduced within the EU with the aim of increasing patient safety by preventing falsified products from entering the pharmaceutical supply chain. The EU Falsified Medicines Directive (2011/62/EU) or EU FMD as it is known, called for a significant overhaul to the existing pharma supply chain system, requiring the establishment and implementation of new organisations and systems needed to authenticate every medicine distributed across the European market.

Initially most of the stakeholder effort was focused on meeting the compliance deadline. For manufacturers this included upgrading productions lines, putting in new IT systems, establishing new processes and running regulatory pack change programmes. Products were generally ready in time across the industry and from 9 February 2019, as per the directive, all packs which were released onto the market carried a two-dimensional (2D) data matrix barcode with a unique identifier (serial number) encoded, along with a tamper evident feature to ensure the integrity of the pack. However, it would be wrong to believe that hitting the compliance deadline was the end of the journey. In many respects, February 2019 was just the starting point for the EU FMD.

Over 130 million prescribed packs are now scanned every single week. The scale of the systems is impressive and the EU FMD has fundamentally changed the way in which prescription medicines are manufactured and how they are managed prior to dispensing. These changes present an even greater challenge than the technical ones already encountered and the implications and impacts are only just starting to surface a year in.

For most of the millions of packs being dispensed each day, the pharmacists receive positive confirmation that the unique identifier is valid and may allow the pack to be dispensed. When this occurs everything runs smoothly, however, not all scans end with a positive confirmation.

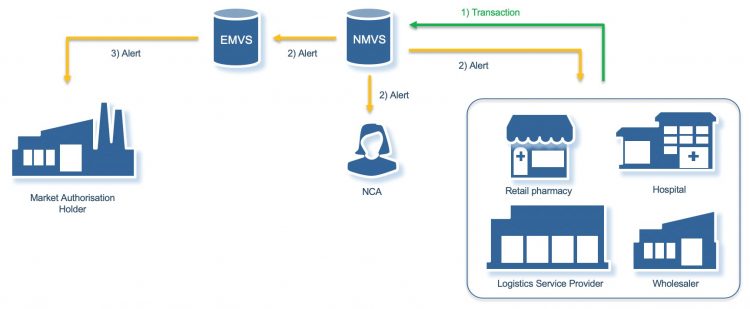

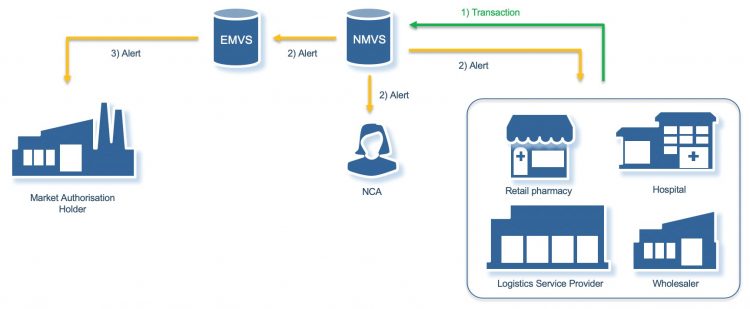

The EU FMD systems are designed to identify any unique identifier on a pack which is not in the system or has a status which means it should not be dispensed. When a pack fails to authenticate, the system generates an alert which is distributed to several stakeholders including an alert to the market authorisation holder (MAH).

[Credit: Grant Courtney/Be4ward].

Alerts generated by the system due to the unsuccessful authentication of a pack are vital as they flag a potential falsified product, allowing action to be taken to address the reason and any potential criminal activity. An alert raises concern over the quality and authenticity of the product, preventing it being dispensed to the patient.

Initially the level of alerts being generated was very high, running at about six percent of all scans. Many of these alerts were false due to two main causes. Firstly, some manufacturers had not managed to upload all the serial numbers into the European Medicines Verification System (EMVS) so missing data was triggering errors. Secondly, the pharmacy systems had not been configured correctly and were introducing errors into the decoded barcode data. These errors included converting upper case characters into lower case and interpreting dates incorrectly.

During the past year, most authorities have taken a lenient view on the alerts, understanding that new software and processes have to stabilise and become embedded. In recognition of this, many operated on a period of stabilisation, whereby packs that triggered an alert could still be dispensed at the discretion of the pharmacist.

Many of these early problems have now been resolved, consequently the level of alerts has reduced to around the one percent mark as an average across EU countries. However, this level is still considered too high with many false alerts continue to take place. It will be progressively more difficult to reduce this further and we can expect this to take many months more to resolve.

With false alerts still in play, if an alert is triggered it is necessary to establish if it is due to a technical or procedural error or if in fact it is due to a suspected falsified product. The need to investigate and resolve alerts is stated as a requirement within the Delegated Regulation and the organisation operating the National Medicines Verification System should provide for the immediate investigation of all potential incidents of falsification (Art 37(d)). Moreover, the EU Q&A document makes specific reference that the National Medicines Verification Organisations should ensure the National Competent Authorities (NCA) are informed as soon as it is clear that the alert cannot be explained by a technical or procedural issue.

The MAH has a role to play in this and must check if it has caused the alert by not uploading the serialisation data or if the data has errors. The expectation is that this resolution should happen within a few days and the relevant NMVO made aware of the outcome of this investigation. In addition, authorities are starting to introduce specific reporting requirements and systems which could vary from country to country.

…EU FMD systems are designed to identify any unique identifier on a pack which is not in the system or has a status which means it should not be dispensed”

The common goal remains that we must reach the point at which an alert prevents a pharmacist from dispensing the medicine to the patient, as dictated by the legislation and with this in mind, several member states have now ended their stabilisation period.

The resolution of alert errors heralds a new phase in the EU FMD journey, where the target is for investigation and resolution of alerts to happen quickly, with the results documented and shared with the NMVOs and authorities. If alerts are caused by technical or procedural issues within the MAH then Corrective and Preventative Actions (CAPAs) need to be executed in alignment with quality procedures and the data uploaded or corrected to resolve the issue before many more alerts are triggered for the same batch. The consequence of not addressing these false alerts is that the flow of goods will stop and product returns could increase.

What should manufacturers be doing and what is coming next?

If manufacturers have not already started, processes and systems must now be put in place to receive, analyse and investigate alerts. The backlog of any alerts that have not been addressed should be cleared and any technical or procedural issues identified and resolved. The regulatory environment should be carefully monitored so that the emerging requirements on alert reporting are captured and built into internal procedures. Regulators are starting to include aspects of the EU FMD within audits and alert management will feature as a topic within these moving forward.

Companies also need to consider how they are going to manage this on an ongoing basis. Tools that have worked for tracking alerts up to now, such as spreadsheets, will reach their technical limit as over time the historical volume of alerts grows. Systems will also have to output to external alert reporting systems operated by the NMVOs and authorities requiring new functionality and potential interfaces.

It is perhaps not surprising that legislation as ambitious as the EU FMD will take some time to achieve its original goal of preventing falsified products from entering the pharmaceutical supply chain. A tremendous start has been made and it is now time to build on this significant foundation and ensure that necessary alert management steps are put in place to allow falsified packs to be correctly identified, only then will the benefits of EU FMD be fully realised.

About the author

Grant Courtney spent 24 years at GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), most recently as its FMD Project Manager and now consults within his area of expertise relating to the interface between patients and healthcare providers and the product, including product coding such as product authentication, patient engagement and mobile health initiatives. Grant also contributes to the shaping of global standards and is an adviser and member of the GS1 Global Healthcare Leadership Team, driving adoption of standards to increase patient safety and lower healthcare costs.

Related topics

Drug Counterfeiting, Drug Supply Chain, Labelling, Packaging, QA/QC, Regulation & Legislation, Supply Chain