Advancing extractables and leachables testing

Posted: 29 April 2022 | Hannah Balfour (European Pharmaceutical Review) | No comments yet

With comment from Diane Paskiet, chair of the Product Quality Research Institute (PQRI) L&E Working Group, EPR’s Hannah Balfour outlines three key exposure-based safety thresholds and explores how the new extractables and leachables (E&Ls) strategy for parenteral drug products was established.

Extractables and leachables (E&Ls) are potentially harmful materials that could be administered to a patient with a drug, and thus are vital to test for and control. While commonly discussed together, there are key differences between the two that are important to understand:

Leachables are organic and inorganic chemicals that can be released from components used in the manufacture and storage of drug products under conditions of normal use (ie, when in direct contact with the drug formulation).

Extractables are organic and inorganic chemicals that are forced out of components under laboratory conditions such as temperature changes, use of solvents or surface exposures. Extractables represent the worst-case scenario regarding chemical release from manufacturing and packaging and can potentially become leachables.

The problem is, “no internationally harmonised guidance on E&L assessment and control exists” that specifically outlines the identification, qualification and reporting thresholds for E&Ls in multiple therapeutic modalities and dosage forms, including addressing safety assessment, the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) highlighted in 2020.2 This, ICH noted, creates uncertainty for industry and regulators that could result in regulatory and patient-access delays.

In October 2021, the Product Quality Research Institute (PQRI) Parenteral and Ophthalmic Drug Products (PODP) L&E Working Group submitted recommendations for E&Ls in parenteral drug products (PDP) to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These recommendations, the culmination of more than a decade of work by the group’s members and collaborators, are now available for the industry.3

To learn more about the PQRI E&L recommendations and the work that enabled their development, as well as why ophthalmic products are not included, European Pharmaceutical Review’s Hannah Balfour met with the Chair of the L&E PDP Working Group, Diane Paskiet, and director of scientific affairs at West Pharmaceutical Services.

developing the guidance was a significant effort, involving more than 100 stakeholders and a colossal amount of data that took years to review”

“Established in 1999, the primary goal of the PQRI E&L working group was to establish safety thresholds and best demonstrated practices for E&Ls in dosage forms that would have a high risk of package-product interaction using science and risk-based approaches,” explained Paskiet. The previous recommendations released by the group were published in 2006, when they provided recommendations to the FDA on safety thresholds and best demonstrated practices for orally inhaled and nasal drug products (OINDP). However, PDPs are also at high risk for interaction and so the group has since worked to develop recommendations of safety thresholds and best practices specifically for drugs administered intravenously (IV), intramuscularly and subcutaneously.

Key takeaways from the new guidance

Paskiet explained that developing the guidance was a significant effort, involving more than 100 stakeholders and a colossal amount of data that took years to review. “The process was further complicated with the advancements made in delivery systems and the new and novel therapies that came out over the decade, especially biologics and combination products,” she added.

Setting thresholds

One of the key aspects of the recommendations is the establishment of three critical exposure-based safety thresholds for PDPs:

- Safety Concern Threshold (SCT) – the level below which a leachable is present at such a low dose that it presents a minimal carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic safety concern to the patient

- Qualification Threshold (QT) – the level below which a leachable is not considered for safety qualification unless it presents structure-activity relationship (SAR) or other safety concerns

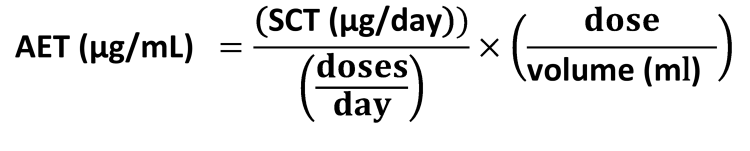

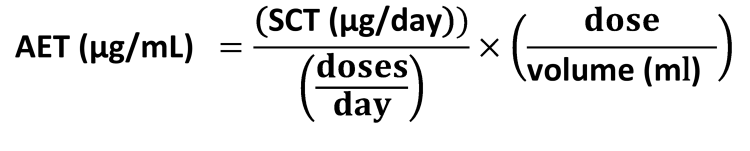

- Analytical Evaluation Threshold (AET) – a calculation that accounts for drug product-dependent parameters, such as dosing and the analytical technique used to produce a particular leachable or extractable, in assessing patient safety. It is calculated using SCT and reflects the level at or above which a chemist should begin to identify a particular leachable and/or extractable and report it for potential toxicological assessment.

Within their studies, the collaborators evaluated more than 600 known potential E&Ls for safety and set the SCT at 1.5 µg/day for most organic leachables, though notable exclusions such as N-nitroso- and alkyl-azoxy compounds will require lower SCTs. The materials studies were released in two separate PDA Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology papers – one in 20134 and the second in 2017.5

In the absence of supporting general toxicology data and an identified potential for irritation or sensitisation, the QT is set at 5 µg/day.

The AET is where things become nuanced and more complex, as the AET changes depending on dose volume per day. The calculation for AET is:

The SCT is 1.5 µg/day for PDPs and if a patient takes one dose per day, the AET has a higher value and results in fewer peaks to be identified. However, if the same drug is taken twice or more per day, the AET value is lower, and the number of peak identifications increases.

Paskiet noted that a critical consideration is that the thresholds outlined in the recommendations are not intended to be control thresholds; “If organic chemicals are above the AET these must be identified and assessed for safety, however certain compounds of concern that would be lower than the AET may need to be specifically targeted,” she said.

![A chromatogram pictorially explaining the Analytical Evaluation Threshold (AET). In the chromatogram, each peak corresponds to a leachable or extractable substance that was present in the test sample and the size of the peak (either its height or its area) is proportional to the amount of that substance that is present in the test sample. A threshold, representing that amount of any individual substance that will not produce an undesirable safety outcome, can be superimposed on the chromatogram as a straight line at its corresponding response level. Those substances whose responses are below the threshold do not have to be considered further (e.g., identified), as their dose will be too low to produce an unacceptable safety outcome. Those substances whose responses are above the threshold have the potential to produce an unacceptable safety outcome [Credit: Image and description adapted from https://doi.org/10.5731/pdajpst.2013.00936].](https://www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/wp-content/uploads/PQRI-Substance-thresholds-chromatogram-750x385.png)

![A chromatogram pictorially explaining the Analytical Evaluation Threshold (AET). In the chromatogram, each peak corresponds to a leachable or extractable substance that was present in the test sample and the size of the peak (either its height or its area) is proportional to the amount of that substance that is present in the test sample. A threshold, representing that amount of any individual substance that will not produce an undesirable safety outcome, can be superimposed on the chromatogram as a straight line at its corresponding response level. Those substances whose responses are below the threshold do not have to be considered further (e.g., identified), as their dose will be too low to produce an unacceptable safety outcome. Those substances whose responses are above the threshold have the potential to produce an unacceptable safety outcome [Credit: Image and description adapted from https://doi.org/10.5731/pdajpst.2013.00936].](https://www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/wp-content/uploads/PQRI-Substance-thresholds-chromatogram-750x385.png)

A chromatogram pictorially explaining the Analytical Evaluation Threshold (AET). In the chromatogram, each peak corresponds to a leachable or extractable substance that was present in the test sample and the size of the peak (either its height or its area) is proportional to the amount of that substance that is present in the test sample. A threshold, representing that amount of any individual substance that will not produce an undesirable safety outcome, can be superimposed on the chromatogram as a straight line at its corresponding response level. Those substances whose responses are below the threshold do not have to be considered further (e.g., identified), as their dose will be too low to produce an unacceptable safety outcome. Those substances whose responses are above the threshold have the potential to produce an unacceptable safety outcome [Credit: Image and description adapted from Paskiet et al. PDA Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology paper available at: https://doi.org/10.5731/pdajpst.2013.00936].

Identifying best practices

In terms of the E&L analysis for PDP, the PQRI recommendations state:

“Extractables assessments and extraction studies for PDP packaging systems should include aqueous-based extraction solvents with appropriate consideration of extraction pH, organic solvent content, and other appropriate extraction conditions (e.g., extraction time, extraction temperature, extraction technique, and sample-to-solvent ratio).”3

Extractables assessments involve extracting chemical entities from a test article (eg, a packaging component or finished packaging system). The extractables are detected via chemical analysis, identified through structural analysis and then quantified. This controlled extraction study and the resulting profiles produce lists of identified and potentially unknown organic and inorganic extractable chemical entities. Extractables profiles are comprehensive datasets that typically include the identity and estimated amount of detectable organic and inorganic extractable chemical entities; an indication of the confidence level in the identification of chemical entities; and supporting analytical data such as chromatograms and mass spectra.

What about biologic and ophthalmic products?

As Paskiet noted, the rise of biological therapies presented a challenge for the working group. Because biologics are well-known for their sensitivity to chemical modification and stability, etc, and often contain a combination of complex substances, “there is still a steep learning curve when it comes to comprehensive understanding of risks for containing and delivering the advancing biological products,” she said.

Biologics present several unique characteristics and challenges with regard to E&Ls. For instance, biologic leachables may not be directly toxic, but they may include chemicals that can react with the drug product to alter its biologic attributes, therefore altering its function and/or safety profile. As a result, the PQRI notes that “comprehensive risk assessments should consider biological activity, efficacy and safety” and methodologies to screen for leachables should consider compounds of toxicological concern as well as those that can impact biological product quality attributes.

To achieve this, methodologies may:

- assess how leachable interactions affect product quality attributes, such as degradation, oxidation, chemical modification, aggregation and immune adjuvant activity

- evaluate the material compatibility, surface characteristics, organic/inorganic alert compounds

- review individual components and system interfaces, performance and functionality

- require leachables assessment performed on the product under accelerated storage/stress conditions and during stability storage.

Due to the complexity of these developing modalities and their container closure systems, the PQRI group recommends interacting early with regulators to get advice on the justifications and documentation for the AET, extraction conditions, extraction solvents and analysis.

Opthalmic drug products were originally expected to be included in the recommendation document, and the L&E Working Group initially set out to study exposure-based safety thresholds for these products, as well. However, ophthalmics presented challenges for safety assessments, including that there was insufficient data on relevant ophthalmic toxicity endpoints. This prevented the group from recommending an SCT, and thus they decided to exclude the product class from the 2022 guidance. However, the working group did publish a separate article outlining science-based practices and key considerations in the analysis, management and safety assessment of E&L in ophthalmic drug products.6

What is the L&E group working on now?

Paskiet explained that the L&E Working Group is now building a series of training courses covering the application of the PDP E&Ls guidelines, including sessions focused on performing the analytical techniques and procedures, as well as the analysis. These will be offered in 2023.

As a result of advancing technology, the future will have a very different outlook, as simulation and modelling enhance our ability to make predictions for E&L early in pharmaceutical development”

Paskiet said the group also is investigating E&Ls relating to novel therapeutics that are beyond the scope of the current recommendations, including messenger RNA (mRNA) and cell and gene therapies, with a view to possibly develop more specific recommendations. A new working group has also been established to identify appropriate E&L practices for combination products that include both a drug and a delivery device.

She also highlighted the role that technology will play in advancing the E&L field: “just like other sectors, extractables and leachables testing will be impacted by digitalisation and automation… As a result of advancing technology, the future will have a very different outlook, as simulation and modelling enhance our ability to make predictions for E&L early in pharmaceutical development. I also believe harnessing data sharing platforms will eventually be transformational for extractables and leachables assessments.” Paskiet noted that the advanced analytics and applied informatics could enable informed decisions and reduce redundant E&L testing in the future.

References

- Guidance for Industry Container Closure Systems for Packaging Human Drugs and Biologics [Internet]. Rockville: US Food and Drug Administration; 1999 [cited 4 April 2022]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/70788/download

- Final Concept Paper ICH Q3E: Guideline for Extractables and Leachables (E&L) [Internet]. Geneva: International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use; 2020 [cited 4 April 2022]. Available from: https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/ICH_Q3E_ConceptPaper_2020_0710.pdf

- Paskiet D, Ball DJ, Jenke D, et al. Safety Thresholds and Best Demonstrated Practices for Extractables and Leachables in Parenteral Drug Products (Intravenous, Subcutaneous, and Intramuscular) [Internet]. Washington DC: PQRI; 2021 [cited 4 April 2022]. Available from: https://pqri.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/PQRI-PDP-Recommendation-2022.pdf

- Jenke D, Castner J, Egert T, et al. Extractables Characterization for Five Materials of Construction Representative of Packaging Systems Used for Parenteral and Ophthalmic Drug Products. PDA Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology [Internet]. 2013 [cited 5 April 2022];67(5):448-511. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5731/pdajpst.2013.00933

- Jenke D, Egert T, Hendricker A, et al. Simulated Leaching (Migration) Study for a Model Container-Closure System Applicable to Parenteral and Ophthalmic Drug Products. PDA Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology [Internet]. 2017 [cited 11 April 2022];71(2):68-87. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5731/pdajpst.2016.007229

- Houston C, Rodrigues A, Smith B, et al. Principles for Management of Extractables and Leachables in Ophthalmic Drug Products. PDA Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology [Internet]. 2022 [cited 11 April 2022];:pdajpst.2022.012744. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5731/pdajpst.2022.012744

Related topics

Analytical techniques, Biologics, Biopharmaceuticals, Drug Safety, Impurities, Manufacturing, Packaging, QA/QC

Related organisations

Product Quality Research Institute (PQRI), US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)