The state of industrial laboratory automation

Posted: 7 April 2008 | Steve Hamilton, Association for Laboratory Automation (ALA), Anne-Kopf Sill, President, ALA and Greg Dummer, Executive Director, ALA | No comments yet

Laboratory automation development is being increasingly outsourced to the commercial market according to a recent industrial member survey by the Association for Laboratory Automation (ALA). ALA polled 400 of its members in industry with 14 questions and received 72 responses representing 47 different companies in the Pharma, Biotech and Agriculture Science sectors (an exceptionally good response). This article discusses the four questions that pertain to how the practitioners of laboratory automation in industry get their job done.

Laboratory automation development is being increasingly outsourced to the commercial market according to a recent industrial member survey by the Association for Laboratory Automation (ALA). ALA polled 400 of its members in industry with 14 questions and received 72 responses representing 47 different companies in the Pharma, Biotech and Agriculture Science sectors (an exceptionally good response). This article discusses the four questions that pertain to how the practitioners of laboratory automation in industry get their job done.

Laboratory automation development is being increasingly outsourced to the commercial market according to a recent industrial member survey by the Association for Laboratory Automation (ALA). ALA polled 400 of its members in industry with 14 questions and received 72 responses representing 47 different companies in the Pharma, Biotech and Agriculture Science sectors (an exceptionally good response). This article discusses the four questions that pertain to how the practitioners of laboratory automation in industry get their job done.

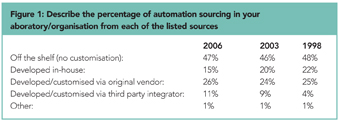

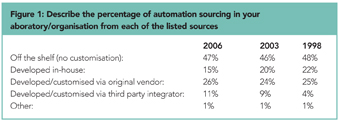

We can compare some of these answers to historical responses to the same question by past attendees of the ‘Introduction to Laboratory Automation’ short course at the annual ALA LabAutomation. The size and diversity of the respondent pool in those cases was similar.

The intuitive question generated by the survey is: “How are we carrying out lab automation today?” Figure 1 shows how ALA members responded:

Over this eight-year period, several trends can be observed. The use of off-the-shelf automation has been relatively constant and therefore approximately half of the lab automation purchased continues to need some level of customisation. The way in which that customisation is achieved is the changing factor. The amount of automation developed in-house has declined; while that developed and customised via a third party integrator has increased since 1998. This is a natural evolutionary trend for any technology, not just lab automation. Early in any technology cycle, development and customisation work is carried out by the ‘gurus’, the tinkerers and early adopters of a given technology. Eventually, sensing a business opportunity, the commercial marketplace responds by offering similar services and tools — often with better quality and at a lower cost – so the need for in-house gurus to tinker lessens.

It is also worth noting that customisation via the original equipment vendor has stayed fairly constant and is the largest single source of customisation. While many vendors would ideally like to just sell ‘boxes’, they can’t get away from the fact that the lab automation business is still very ‘custom-driven’. Despite the fact that today’s off-the-shelf lab automation is increasingly sophisticated and feature-rich, no lab is exactly the same and customisation is still in great demand.

There is a modest trend toward more organisations employing in-house expertise, which is interesting in light of the trend toward less in-house customisation. Just because more work is being ‘farmed out’ doesn’t mean that internal expertise is not needed, but those internal experts may be spending more of their time managing outsourced projects than in the past. Managing a complex external project is still very time consuming, however. These results may also indicate that the customisation work remaining to be done in-house is the ‘high-hanging fruit’, i.e. they are difficult tasks requiring more resources, not less. Alternatively, this may simply reflect that the growing amount of automation in laboratories requires more staff to devote time to programming, reconfiguring, tweaking and maintaining existing automated tools, but not actually creating new automated systems.

It should be noted that this question only gets at the presence of internal resources, not the number of internal resources — which is a very difficult thing to quantify in a survey. This survey did not reach companies without ALA members – companies with a potentially lesser commitment to automation technology. However, it is still apparent that the industries represented in this survey are technology-driven industries and, as such, they continue to employ resources to manage that technology drive.

There are substantial percentages representing each style of support. While outsourcing is the single largest source of support, more than half of the total support is still provided by internal resources. This may again be a reflection of the highly customised nature of the final installations of much lab automation.

Given the highly independent nature of laboratory scientists, it is surprising that the ‘‘Yes’’ number is as high as it is. While IT groups have long been successful at telling scientists which office computer they were going to use, the same scientists usually bristle at restrictions on what goes into their laboratory. The fastest way to bog down internal automation development resources is with on-going support responsibilities, so perhaps these numbers reflect an attempt by such resources to keep their head above water and/or make outsourcing more effective? Certainly, outsourcing support is easier if an organisation owns a critical mass of equipment from a given vendor.

Steve Hamilton

Association for Laboratory Automation (ALA)

Steve Hamilton, Ph.D., is a Founder and Charter Member of ALA. After years in the drug discovery world, heading many leading-edge automation projects for companies such as Eli Lilly, Scitec and Amgen, Steve now has his own consulting firm (Sanitas Consulting, Boulder, CO). He received his Ph.D. in Analytical Chemistry from Purdue University and a B.S. in Chemistry from Southeast Missouri State University. Steve is the recipient of many prestigious awards, including the 1986 Pioneer in Laboratory Robotics Award and others.