Developing OTC syrup packaging for the highly regulated EU market

Posted: 21 August 2017 | Piotr Zaborniak | No comments yet

The regulatory environment has a great impact on business, especially in healthcare. Non-compliance exposes companies to the risk of launch delay, delisting products from the market and out-of-stocks. Moreover, it can cause reputational damage affecting staff, consumer and shareholder confidence, reduce market opportunities, and affect the bottom line.

Before being placed on the EU market, all new pharmaceuticals must be authorised by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) or national agencies. Directive 2001/83/EC on medicinal products for human use provides a number of requirements to be met within the medicinal product specifications. The directive lists all relevant particulars, as well as documents that should be included in the application together with printed mock-ups and results of a legibility assessment carried out with patients from the target group. The following information should be provided in the application dossier for each pack:

- Packaging size

- Description of the container, closure system and administration device including the identity of each immediate packaging material and their specifications

- Documented compatibility of the finished product with the dosage devices.

The Medical Devices Directive (MDD) requires that all medical devices (MD) that are being placed on the market and/or put into service must bear the CE mark of conformity. The mark must consist of the initials ‘CE’ in the form presented in Figure 1 with respect to the given proportions, and the components of the marking should have the same vertical dimensions with a minimum of 5mm. For ‘Class I MD with Measuring Function’, EC the marking must be accompanied by the identification number of the body that has performed the conformity assessment.

Figure 1: CE mark design

Packaging information requirements

All medicinal products placed on the Common Market must be accompanied by labelling and a package leaflet that provide comprehensible information enabling their safe and appopriate use. Artwork on either outer packaging and/or immediate packaging (labelling) or package leaflet should allow sufficient space for the particulars required by Directive 2001/83/EC to appear. The directive allows a package leaflet to be omitted where all required information can be directly conveyed on the packaging.

All information about the required particulars has been summarised in Table 1 they should appear in an official language (or in all official languages) of the marketed country. The information should be easily legible, clear, easy to use, clearly comprehensible and indelible, and should reflect the results of consultations with target patient groups. The design and layout recommendations for making artworks legible has been reviewed in Table 2

Table 1 : Medicinal product information – required particulars (2001/83/EC)

Click image to open larger version in a new window

1 For orphan medicinal products the outer packaging information may appear in only one of the official languages of the community – on reasoned request

2 Where there is no outer packaging, the relevant information should appear on the immediate packaging

3 Member states may require certain forms of labelling of the medicinal product – these requirements are listed by Member State in Annex I to Guideline on the packaging information of medicinal products for human use authorised by the union (EMA, 2011)

4 Inclusion in the packaging of all medicinal products of a package leaflet should be obligatory unless all the information required to appear on the leaflet can be directly conveyed on the outer packaging or on the immediate packaging

5 Common name shall be included where the product contains only one active substance and if its name is and invented name

6 As appropriate, depending on the nature of product

7 For medicinal products that are authorised subject to additional monitoring for reasons of their specific safety profile (medicinal products with a new active substance, biological medicinal products and products for which post-authorisation data are required) the following statement should appear: This medicinal product is subject to additional monitoring, preceded by the symbol of black inverted equilateral triangle, proportional to the font size of the subsequent standardised text (each side of the triangle should have a minimum length of 5 mm (EC/726/2004; EU/138/209)) and followed by an appropriate standardised explanatory sentence

8 Marketing authorisation holder shall ensure that the package information leaflet is made available on request from patients’ organisations in formats appropriate for the blind and partially-sighted

9 Particular Member State may require the use of certain form of labelling – the information specific to a Member State should be accommodated on the label in a single boxed area, with a blue border – so-called ‘blue box’, to appear on one side of the pack (when in exceptional circumstances, several ‘blue boxes’ are required for the different Member States – they should ideally have the same dimensions and appear on the same side of the pack)

10 Guideline on readability of the label and package leaflet of medicinal products for human use (EC, 2009) – BRAILLE

11 Where the medicinal product contains up to three active ingredients, the INN/common name(s) of these active ingredient(s) should be stated after the full name on the outer packaging and the immediate packaging, unless the INN/common name(s) is part of the name

12 Where space is at premium the shortened term for pharmaceutical form, as stated in the in the list of EDQM “Standard Terms” may be used on small immediate packaging (https://standardterms.edqm.eu/)

13 Containers of nominal capacity of 10ml or less

PACKAGE LEAFLET | LABELLING (covers both – outer and inner packaging) | |||

Type size and font | Font easy to read, not stylised, similar letters/numbers should be easily distinguished from each other (e.g. “i”, “l”, “I” and “1”) | X | X | |

Minimum size of 7 points (or of a size where the lower case “x” is at least 1.4 mm in height), leaving a space between lines at least 3 mm | X | |||

Minimum size of 9 points, as measured in font ‘Times New Roman’, not narrowed, with a space between lines at least 3 mm | X | |||

Sufficiently large font should be used for printing to ensure maximum legibility of the information | ||||

Colour for the text on blister foil should be chosen carefully as the legibility of the text on the foil is already impaired due to the nature of the material | ||||

Different text sizes to enable key information to stand out and to facilitate navigation in the text (e.g. for headings) | X | X | ||

Larger type size should be used where a medicinal product is especially intended for an indication linked to visual impairment | X | X | ||

Lower case should be used for large blocks of text, however capitals may be useful for emphasis | X | |||

Italics or underlining should not be used, however italics can be used for Latin terms | X | X | ||

Design and layout of the information | Outer packaging must include space for the prescribed dose to be indicated and/or “blue box” | X | ||

“Justified” text should not be used | X | |||

Space between one line and the next should be at least 1.5 times the space between words on a line | X | |||

Company logos and pictograms may be presented, where space permits, on the outer packaging and on immediate packaging, provided they do not interfere with the legibility of the mandatory information | X | |||

Important information should be clearly mentioned on prime spaces on the outer and immediate packaging, presented in a sufficiently large type size | X | |||

Line-spacing and white spaces should be used to enhance the legibility of the information provided | X | |||

Use of any innovative technique in packaging design to aid in the identification and selection of the medicinal product is encouraged, especially where space is at a premium | X | |||

Text should be contrasting to the background; no background images should be placed behind the text | X | X | ||

Column format should be used – the margin between the columns should be large enough to adequately separate the text (if space is limited a vertical line to separate the test may be used) | X | |||

Related information should be kept together so the text flows easily from one column to the next | X | |||

Landscape layout is recommended for the sake of patients’ convenience | X | |||

For multi-lingual leaflet clear demarcation should appear between different languages used | X | X | ||

Headings | Bold type face or a different colour should be used for heading | X | X | |

Spacing above and below the heading should be consistently applied throughout the leaflet | X | |||

Same level headings should appear consistently (numbering, bulleting, colour, indentation, font and size) | X | |||

It is recommended not to use more than two levels of headings, however this might be needed to communicate complex information | X | |||

Lines can be used as a navigation tool to separate different sections within the text | X | |||

Sub-headings and associated text from the Product information template should be included only if they are relevant for the particular medicine – other sections can be omitted from the package leaflet | X | |||

Paper | Paper weight chosen should be such that the paper is sufficiently thick to reduce transparency; use of uncoated paper is recommended as glossy paper reflects the light making information difficult to read | X | ||

When leaflet is folded, creases should not interfere with the readability of the information | X | |||

Print colour | Different type colour can be used to make headings or other important information clearly recognisable | X | X | |

Dark text should be printed on a light background or light text on a dark background; similar colours should not be used for the text and background as legibility is impaired | X | X | ||

Highly glossy, metallic or reflective packaging should be avoided, as this affects the legibility of the information; different colours in the name of the product are discouraged since they may negatively impact on the correct identification of the product name | X | |||

The use of different colours to distinguish different strengths is strongly recommended | X | |||

Similarity in packaging which contributes to medication error can be reduced by the judicious use of colour on the pack (where colour is used on the outer pack it is recommended that it is carried onto primary packaging to aid identification of the medicine) | X | |||

where possible, nonreflective material or coloured foils should be considered to enhance the readability of the information presented and the correct identification of the medicine | ||||

colour for the text on blister foil should be chosen carefully as the legibility of the text on the foil is already impaired due to the nature of the material | ||||

Syntax | simple words of few syllables should be used if possible | X | X | |

it is better to use a couple of sentences rather than one longer sentence, especially for new information | X | X | ||

for lists (such as list of side effects) bullet points should be used; where possible, no more than five or six bullet points should be used | X | |||

side effects should be set out by frequency of occurrence, starting with the highest frequency | X | |||

Style | active style should be used instead of passive | X | X | |

instruction should be followed by reasoning | X | X | ||

instead of repeating name of the product – “your medicine, this medicine, etc.” should be used | X | X | ||

abbreviations and acronyms should not usually be used unless these are appropriate; when first time used in text, the meaning should be spelled out in full; scientific symbols should not be used | X | X | ||

medical terms should be translated into language which patients can understand | X | X | ||

General considerations | Items critical for the safe use of the medicine: | X | ||

different strengths of the same medicinal product should be expressed in the same manner; trailing zeros should not appear; the use of decimal points should be avoided where these can be removed; for safety reasons it is important that micrograms are spelt out in full and not abbreviated (however, in certain instances where this poses a practical problem which cannot be solved by using a smaller type size then abbreviated forms may be used, if justified and if there are no safety concerns) | X | |||

regarding route of administration, negative statements should not be used; in principle only standard abbreviations may be acceptable (i.v., i.m., s.c.) – in addition, a list of other, non-standard abbreviations which can be used in labelling is published on the EMEA website – other nonstandard routes of administration should be spelled out in full; some routes of administration will be unfamiliar to patients and may need to be explained within the package leaflet. This is particularly important when medicinal products are made available for self-medication | X | |||

Symbols and pictograms | symbols and pictograms should be used only to aid navigation, clarify or highlight certain aspects of the text – they should not replace the actual text | X | X | |

Product ranges | there should, in principle, be a separate leaflet for each strength and pharmaceutical form of a medicinal product; on a case-by-case basis national competent authorities or the European Commission may however agree to allow the use of combined package leaflets for different strengths and/or different pharmaceutical forms (e.g. tablets and capsules), for instance where achieving a recommended dose necessitates a combination of different strengths, or when the dose varies from day to day depending on the clinical response | X | ||

simple reference to other strengths and pharmaceutical forms of the same medicine is always possible if necessary for the therapy – for instance, referring to a different strength, or referring in the package leaflet of a tablet which is unsuitable for children to the availability of an oral solution for children | X | |||

Products administered by a healthcare professional or in a hospital | for a product administered by a healthcare professional, information from the summary of product characteristics for the healthcare professional (e.g. the instructions for use) could be included at the end of the patient leaflet e.g. in a tear-off portion, to be removed prior to giving the leaflet to the patient (alternatively the complete summary of product characteristics could be provided in the pack along with the package leaflet) | X | ||

for a product administered in hospital additional package leaflets (in addition to the one provided in the pack) may be made available on request to ensure that every patient receiving the medicine has access to the information | X | |||

Table 2 Design and layout recommendations for making artwork legible (2001/83/EC; EC, 2009)

Although medicinal product packaging can be presented in several linguistic and/or ‘national’ versions, when a product is marketed in more than one country, the logo, format, layout, style, colour scheme and pack dimensions (if possible) should be identical for all the versions of packs throughout the EU. This regulation shall not prohibit the use of two or more commercial designs for a given medicinal product covered by a single marketing authorisation; this should be discussed with EMA from the practical application point of view, however.

The denomination of the drug is legally required to be in Braille on the secondary/outer packaging, and the package leaflet must be available on request in formats for the blind and partially-sighted patients. Information required in Braille on the packaging consists of the medicine’s trade name of the medicinal product followed by the product strength. Further information, such as expiry date, pharmaceutical form, target patient age group, international non-proprietary names or common names of active ingredients (up to three APIs) are optional for the bigger volume packs to appear in Braille.

Information in Braille does not have to be on the immediate packaging, as long as there is outer/secondary packaging (such as a carton), otherwise an adhesive Braille label can be attached around the immediate packaging. There is no need to dedicate blank space on the artwork for information in Braille, but legibility of the underlying text should be taken into consideration. Generally, the uncontracted Braille system and Marburg Medium Braille font standard are recommended. However, in the case of small-volume packaging (up to 10mL), contracted Braille or certain defined abbreviations can be used; alternatively, a supplementary ‘tab’ label can be applied.

‘Falsified medicines’ are fake medicines that pass themselves off as real, authorised medicines, unlike so-called ‘counterfeits’, which infringe intellectual property rights. To ensure that medicines are safe and trade is rigorously controlled, the Falsified Medicines Directive set up new requirements for safety features: a unique identifier (a serial code in the 2D barcode) and anti-tampering device to appear on the outer packaging of prescription medicines. However, medicinal products not subject to prescription need not bear safety features unless listed in the delegated act based on a falsification risk assessment.

Unless it is obvious, each medical device placed on the market should have its intended purpose clearly stated on the label and should be accompanied by information about its safe and proper use, ideally using symbols and colours conforming to the harmonised standards, and providing information to identify the manufacturer on the label and in the instruction of use.

Design considerations

According to MDD applicable to ‘Class I MD with Measuring Function’, devices must be designed, manufactured and packaged:

- For patient safety

- For lay, professional, disabled or other users

- In a way that meets their primary function (eg, measuring) over lifetime

- In a way that provides sufficient accuracy and stability

- In line with ergonomic principles for measurement

- In line with requirements regarding units of measure – either ml or mL

- To minimise risk of infection to patient, user and third parties.

The evaluation of meeting these criteria must be based on clinical data. However, according to MDD this does not have to be a full clinical study and critical evaluation of the scientific literature related to safety, performance, design characteristics and intended purpose of the device is sufficient as long as equivalence can be demonstrated.

Child-resistance and senior-friendliness requirements

Child-resistant packaging is defined as: “package which is difficult for young children to open (or gain access to the contents), but which it is possible for adults to use properly” (EN 14375). There are no consistent rules in this matter for drugs and medical devices in the EU, however some member states have laid down their own country-specific laws – UK, Germany, Italy and Netherlands.

All packages for medical products falling under child-resistant and senior-friendly (CRSF) requirements have to meet standard EN ISO 8317 for reclosable packaging, or EN 14375 for non-reclosable packaging, but both describe the protocol to follow to test packaging with both children and adults. Certificates of CRSF compliance can be issued only by accredited test laboratories.

Child resistance is a factor of the whole packaging system, therefore container and closure must be tested together (with placebo formula). The test protocol depends on the tested packaging and packaged product, but there is no requirement to repeat the test for every geometry of the pack. For the range of reclosable packaging (bottles with different capacity) with the same neck finish and diameter, as well as sharing the same child-resistant closure, only the smallest and largest package need to be tested and the results can be extrapolated for all intermediate packaging sizes. In order to check the probability of CRSF compliance to minor modifications to the non-reclosable packaging, materials can be checked for their puncture resistance, bursting strength, and sealing strength. For reclosable packaging, manufacturers can use mechanical tests for different types of packs, such as testing the force needed to push, pull or squeeze a bottle closure.

The European Pharmacopoeia gives the requirements for filling volume to be determined as maximum 90% of brimful capacity of the container. On top of that, to prevent misleading or deceptive packaging being placed on the market, the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive put in place a requirement that packaging’s outward appearance cannot mislead consumers about the factual quantity of the product. For example, in Germany the permitted free space of a package should not exceed 30%.

Material compliance considerations

Glass is considered to be inert and is covered in European Pharmacopoeia (Ph Eur). It should not release any substances in quantities sufficient to affect the stability of the preparation or to present a toxicity risk, so its composition of the glass should be known so that the potential hazard can be assessed. Apart from that, migration tests are not required. Ph Eur lists three types of glass, with the recommended applications based on their chemical characteristics. On top of that, Ph Eur allows the use of coloured glass for substances that are known to be light-sensitive. However, it recommends that all glass containers for liquid preparations permit visual inspection of the content. Another pharmacopoeial recommendation is that glass containers are not to be re-used (with exceptions). To define the quality of glass containers according to the intended use, Ph Euro recommends performing relevant tests to given limits with its methods.

The use of plastic materials for containers and closures for medicinal products has been very well described in the European Pharmacopoeia. The following polymers are described in the Ph Eur and can be used in primary packaging for non-solid, orally distributed medicinal products:

- Polyolefins

- Polyethylene (with and without additives)

- Polypropylene

- Poly(vinyl chloride)

- Poly(ethylene terephthalate)

- Poly(ethylene-vinyl acetate)

When selecting suitable plastic for primary packaging it is crucial to know the full manufacturing formula, including all materials added during the formation process, so that potential hazards can be assessed. Any ingredient of the medicine in contact with the plastic should not be able to adsorb significantly on its surface or migrate into or through plastic. Plastic material cannot release substances to the medical preparation in quantities sufficient to affect its stability or to present a toxicity risk. This must be examined during compatibility studies of packaging with the final medicinal formulation, including pH changes, verification of the absence of changes in physical characteristics, assessment of any loss or gain through permeation, assessment of changes caused by light and any other chemical test as well as biological tests when appropriate.

The list of materials presented in Ph Eur is not exhaustive, and any materials of polymers other than those described may still be used subject to approval by the competent licensing authority. According to the Guideline on Plastic Immediate Packaging Materials, to introduce a new immediate plastic packaging for medicinal products, all materials need to be thoroughly investigated and test results provided in the application form. This is limited only to plastic materials in direct contact with the active substance or medicinal product, whenever this material is a part of a container, closure, seal or other part of the container closure system. The required data should be collected during the development of a drug and presented to justify the choice of the plastic material in relation to the stability, integrity and compatibility of the medicinal product, method of administration and to any sterilisation procedures, if applicable.

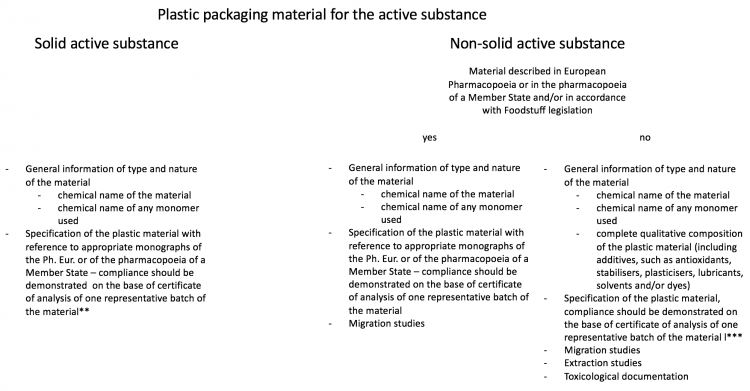

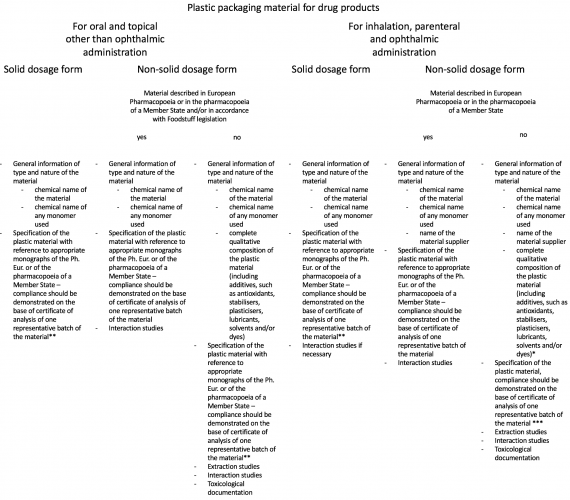

Data to be provided for those packaging materials depends on the physical state of the pharmaceutical dosage form and route of application of the medicinal product. How it differs is presented in. On top of that, the European Pharmacopoeia requires all materials intended to be in contact with medicinal formula to undergo risk assessment with respect to transmissible spongiform encephalopathy – TSE (including bovine spongiform encephalopathy – BSE) and to take all suitable measures to minimise such risk.

Table 3: Plastic Materials Compliance – requirements (EMA, 2005)

Click images to open larger version in a new window

* complete qualitative composition of the plastic material should be also provided in cases where monograph authorises the use of several additives from which the manufacturer may choose one or several in defined limits.

** If plastic material is not described in neither European Pharmacopoeia nor pharmacopoeia of a Member State, an in-house monograph has to be established according to the following list, taking into account the general methods of the pharmacopoeia

- description of the material

- identification of the materials

- characteristic properties, e.g. mechanical, physical paramaters

*** an in-house monograph needs to be established according to following list, taking onto account the general methods of the pharmacopoeia

- description of the material

- identification of the materials

- characteristic properties, e.g. mechanical, physical paramaters

- identification of the main additives, in particular those which are likely to migrate into the contents (such as antioxidants, plasticisers, catalysts, initiators, etc.)

- identification of colorants the nature and amount of extractables, based on the results of the extraction studies

For materials not covered by the Pharmacopoeia, or when Ph Eur grade material is not available, food-grade material is accepted after thorough migration studies and toxicology review. Food-grade material by nature has to be compliant with the directive on plastic materials and articles intended to come into contact with food.

General packaging and packaging waste regulation should not be forgotten either, since it is a standard for all kinds of packaging and describing, eg, maximum content of heavy metals in the packaging material. The range of additives (antioxidants, stabilisers, plasticisers, lubricants, colourants, impact modifiers, antistatic agents and mould-release agents) has been also mentioned in the European Pharmacopoeia, however without specific measures or limits to follow.

According to MDD, devices intended to administer medicinal products must be designed and manufactured so as to be compatible with the relevant medicinal products and reduce to a minimum the risk posed by substances leaking from the device, as well as by the unintentional ingress of substances into the device. Special actions should be taken if device resin material contains phthalates, which are classified as carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic to reproduction, and in such cases phthalates containment should be indicated on the packaging label. To be compliant with MDD bio-compatibility of some medical devices should be also taken into consideration.

Conclusions

At the moment, few topics have not been covered by European Union regulations, despite suggestions from the industry. These concerns are as follows:

- Tamper-evidence on the primary packaging is not a mandatory requirement either for food, medicines nor medical devices. An anti-tampering solution is mandatory only on outer packaging for prescription medicines.

- It is not clear whether parts of packaging and medical devices must follow toys safety directive regulating prevention of choking-hazard for children. There are no specific requirements for packaging for paediatric medicines.

- The majority of EU countries have not introduced any CR requirements for non-prescription medicines, and the ones that have implemented the regulations for CR are not rigorous enough. One industry suggestion is that it should be based on calculated PHA (Potential Harmful Amount) and Failure (F) value as required by the FDA and practised in USA.

- Criteria for bio-compatibility tests for medical devices are not clear and are left to the interpretation of the medical device manufacturer.

- Misleading or deceptive packaging assessment rules are not unified in the EU and depend on each country’s regulations.

Acknowledgments

This article was written in cooperation with the NVC Netherlands Packaging Centre. NVC (founded in 1953) is the association of companies addressing the activity of packaging throughout the supply chain of packaged products. The NVC membership, projects, information services and education programme stimulate the continuous improvement of packaging.

BIOGRAPHY

Piotr Zaborniak is Global Packaging Development Manager at GSK Consumer Healthcare, based in Switzerland. Prior to GSK, he worked at RB in various product and process development roles. He graduated from Warsaw University of Technology, Warsaw School of Economics and The Institute of Materials, Minerals and Mining in UK. Email: [email protected]. Tel: +41(0) 79 797 86 79