Solid-state NMR spectroscopy: predicting stability in lyophilised biological products

Posted: 2 November 2018 | Ashley Lay (University of Kentucky), Eric J. Munson Professor and Head of the Department of Industrial and Physical Pharmacy at Purdue University, Yongchao Su (Associate Principal Scientist in Pharmaceutical Sciences-Merck) | No comments yet

The emergence of biological drugs has led to an increase in lyophilised drug products in the market. Lyophilisation is a technique used to stabilise parenteral formulations in a solid form with the goal of producing chemically and physically stable, homogeneous, and high-quality lyo-products.

The processes of freezing a formulation, followed by sublimation of the solvent to produce a lyo-cake, is extremely complicated, and demands further investigation of formulation design, stability, cycle development, and process scale-up to produce the highest quality lyo-product.

Proteins can be difficult to formulate as both chemical and physical stability must be considered. The protein needs to be formulated so that chemical degradation, such as deamidation, does not occur, whilst also assuring that the secondary and tertiary structure of the protein is stabilised against unfolding.1 Lyophilised formulations typically contain disaccharide sugars, such as sucrose or trehalose, both to stabilise the protein from unfolding and to create a glassy matrix. Low amounts of buffers are also added for ionisation control.

Most proteins will behave differently from each other and require extensive research in order to identify the ratios of the excipients that lead to the “most stable” formulation. The formulations are typically ranked for stability by using accelerated temperature and/or humidity conditions to force the degradation of the protein. These require significant investment, as the studies run for weeks to months and require a battery of testing including techniques to determine changes that may be indicators of decreased stability, such as secondary and tertiary structure, high or low molecular weight species, and pH.

There are two main hypotheses related to stabilisation through freeze-drying: water replacement and vitrification. The water replacement theory states that sugar hydrogen bonds with the protein as the water leaves during sublimation, while the vitrification theory states that reducing the motion of the protein aids in stabilisation.2 It is likely that both theories play a role in stabilisation. Nevertheless, analytical techniques capable of characterising lyophilised pharmaceuticals are needed to study the stability of these proteins by investigating the molecular, structural and dynamic properties of lyocakes in the solid state.

Analytical techniques for characterising lyophilised pharmaceuticals

Ideally, it would be useful if a technique could characterise the structural properties of the time zero samples and use this information to predict long-term stability. Common solid-state techniques are typically used to characterise lyophilised cakes, including: differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), circular dichroism (CD), powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), and Raman spectroscopy. PXRD is used to look for crystallinity of excipients and to identify polymorphs of crystallising excipients, such as mannitol.3 FTIR and CD are used to look for changes in secondary structure of proteins as the formulation is aged. While changes in secondary structure may impact stability, there have been reports of no change in secondary structure despite there being stability differences.4 Raman mapping techniques have been developed to look for phase separation between the stabilisers and the proteins. This technique is limited to detection of phase separation in the micron range.5,6 DSC is used to measure the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the solid. A higher glass transition temperature corresponds to a lower degree of global mobility within the solid matrix. DSC can also be used to look for phase separation, as multiple Tgs are observed if there is a protein-rich region and a sugar-rich region.7 Dried proteins show a minimal change in heat capacity, so it is hard to detect a protein-rich region in the solid-state lyophilised product.8

Looking at local motion, or beta-relaxation, has become more common, as these fast motions are on the same time scales (picoseconds to nanoseconds) as movement in protein side chains and diffusion of small reactive species.9 Neutron back scattering and dielectric relaxation can both be used to monitor this local mobility in a solid. Decreases in local motion as measured by neutron back scattering have been shown to correlate with increased stability.10 Unfortunately, neutron back scattering is not a commercially available characterisation technique and is not feasible for routine use in the pharmaceutical industry. A technique that is more readily available in pharma and capable of measuring local mobility is solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (SSNMR). Table 1 shows the common solid state characterisation techniques and what they are capable of measuring. SSNMR has the added benefit of being capable of also looking at ionisation changes, polymorphic form, crystalline vs. amorphous quantitation, and miscibility, in addition to local mobility.

Using solid-state NMR spectroscopy to predict stability

SSNMR is useful for monitoring multiple stability issues in lyophilised cakes including: changes in ionisation, phase separation and mobility.

Ionisation

During the freezing process, ice crystallises first and creates super-saturated pockets of water, stabiliser, drug, and buffer. While cryoprotectants like sucrose or trehalose have been shown to inhibit most crystallisation within the formulation, buffer salts may partially or fully crystallise during freezing.11 Changes in ionisation of the solution before it is fully frozen could lead to potential denaturation of the protein. It can, however, be difficult to determine if any ionisation changes or degradation have occurred in the lyophilised solid; pH can be monitored in the frozen solid, but most low temperature pH electrodes have a lower temperature limit of -25°C.12 Microenvironment pH cannot be directly measured in the solid cake, so previous studies have used pH indicators to look for changes in ionisation in the final lyophilised product.13 The pH indicator method, however, has a few limitations. One is that it is difficult to determine if the pH indicator is in the same phase as the protein; and another is that the ionisable groups are often very different to those found in proteins. Different ionisable groups can have different changes in ionisation as temperature is decreased.12 SSNMR could be highly useful in lyophilised formulations to detect ionisation. 13C labelling can be employed in two different ways: using a 13C labelled probe that has a similar ionisable group to the protein, or directly 13C labelling the ionisable group of interest in the protein. This method could be used to more rapidly buffer screen lyophilised formulations by choosing the formulation that leads to the least amount of ionisation change of the probe or protein.

Miscibility and mobility

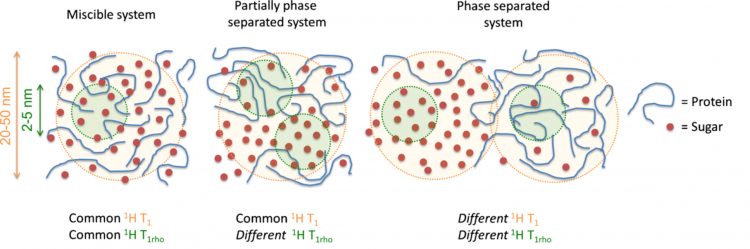

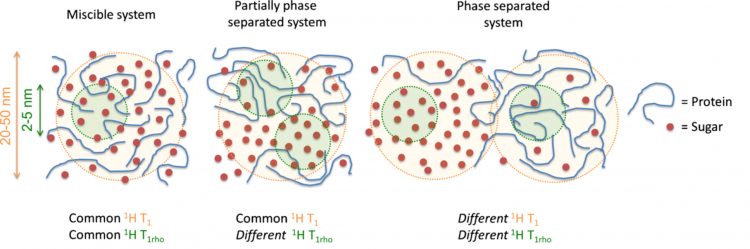

Proton spin-lattice relaxation times (1H T1 and 1H T1ρ) give insight to dynamics and miscibility within the freeze-dried matrix. Proton spin lattice relaxation times (1H T1) measure motion on the ps-ns time scale and proton spin lattice relaxation times in the rotating frame (1H T1ρ) measure motion on the ms-ms time scale. Protons exchange spin polarisation through a process known as spin diffusion, which allows for calculation of domain sizes from relaxation measurements.14 These domain sizes correlate to around 20-50nm and 2-5nm domain sizes, for 1H T1 and 1H T1ρ measurements.15 Miscibility is determined by measuring and comparing the 1H T1 and 1H T1ρ times for the two components. If the components have similar T1 and T1ρ times, the components are close enough for magnetisation to be transferred between the nuclei and are said to be miscible down to 2-5nm. If the components have the same T1 but differing T1ρ times, the system is miscible down to 20-50nm. If both the T1 and T1ρ times for the components are different, the system is phase separated as shown in Figure 1. This method has been used in sugar-IgG systems where it was found that trehalose was miscible with the model protein (IgG). The trehalose formulation was more stable by SEC and ELISA measurements than larger sugars (dextrans and inulins), which were shown not to be miscible down to the 2-5nm range.16 It has also been shown by 1H T1 measurements that trehalose was miscible with lysozyme while lactose phase separated from the lysozyme.9 Additionally, the relaxation time values have also been shown to correlate with stability. Longer relaxation times correspond to a more rigid system, ie, less mobility. Adding lactose and trehalose to lysozyme increased the lysozyme 1H T1.9 The T1 relaxation times for the protein correlated with aggregation rates for a model IgG formulated with potential stabilisers.16 It appears from these studies that miscibility between protein and sugar at the 2-5nm level is an indicator of stability. If multiple excipients are miscible with the protein, then the magnitude of the relaxation time becomes important and the formulation with the longest relaxation time may be the most stable.

Figure 1: Degree of miscibility can be determined using SSNMR proton spin-lattice relaxation times, 1H T1 and 1H T1ρ. Figure reproduced from Mensink et al.16 Copyright 2016 The AAPS Journal

Molecular conformation

Protein structure is a critical molecular property for bioavailability and stability. Interactions with excipients, water sublimation, ionisation and thermal stress during lyophilisation cycles can potentially impact protein conformations and thereby affect activity. It is technically challenging to investigate conformational change, particularity in a residue-specific manner. SSNMR has been utilised for structural elucidation of insoluble biomacromolecular systems including: crystalline proteins, membrane-active peptides, ion channels, protein assembly and amyloid fibrils.17 Recent advances in techniques of sensitivity enhancement, including dynamic nuclear polarisation (DNP) and ultrafast magic angle spinning (UF-MAS, 60-110kHz), provide a great potential for SSNMR to characterise structures and interactions of natural abundance pharmaceutical formulations.18-20 The significantly boosted intensity enables multidimensional spectroscopy for resolving the site-specific information. High-resolution characterisation of structural perturbation can be achieved by sequential chemical shift analysis for evaluating the conformational stability of lyophilised products.

Conclusion

Making a suitable, stable lyophilised protein product and bringing it to market is an expensive and time-consuming process. SSNMR is useful for investigating the ionisation, miscibility, and mobility of a protein formulation in the solid state; these are factors that show correlations with stability, which could lead to improved formulations for lyophilised products.

Disclosure

Eric Munson is a partial owner of Kansas Analytical Services, a company that provides solid-state NMR services to the pharmaceutical industry. This review is based on his academic work at the University of Kentucky, and no data from Kansas Analytical Services is presented here.

Techniques | Pharmaceutical and structural properties | |||||

Crystallinity | Polymorphic Form | Miscibility | Ionisation Changes | Mobility | Protein Structure | |

Differential Scanning Calorimetry | x |

| x |

| x |

|

Powder X-Ray Diffraction | x | x |

|

|

|

|

Neutron Scattering | x | x |

|

| x |

|

Dielectric Spectroscopy |

|

|

| x |

| |

Raman Spectroscopy | x | x | x | x |

|

|

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy | x | x |

| x |

| x |

Circular Dichroism |

|

|

|

|

| x |

Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy | x | x | x | x | x | x |

Table 1: Solid-state analytical tools for assessing lyophilised formulations

References

- Manning MC, Patel K, Borchardt RT. STABILITY OF PROTEIN PHARMACEUTICALS. Pharmaceutical Research. 1989. 6(11): p. 903-918.

- Cicerone, MT, Pikal MJ, Qian KK. Stabilization of proteins in solid form. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2015. 93: p. 14-24.

- Jena S, Suryanarayanan R, Aksan A. Mutual Influence of Mannitol and Trehalose on Crystallization Behavior in Frozen Solutions. Pharmaceutical Research. 2016. 33(6): p. 1413-1425.

- Cleland JL, et al. A specific molar ratio of stabilizer to protein is required for storage stability of a lyophilized monoclonal antibody. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2001. 90(3): p. 310-321.

- Padilla AM, Pikal MJ. The Study of Phase Separation in Amorphous Freeze-Dried Systems, Part 2: Investigation of Raman Mapping as a Tool for Studying Amorphous Phase Separation in Freeze-Dried Protein Formulations. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2011. 100(4): p. 1467-1474.

- Forney-Stevens KM, et al. Optimization of a Raman Microscopy Technique to Efficiently Detect Amorphous-Amorphous Phase Separation in Freeze-Dried Protein Formulations. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2014. 103(9): p. 2749-2758.

- Izutsu K, et al. Impact of heat treatment on miscibility of proteins and disaccharides in frozen solutions. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics. 2013. 85(2): p. 177-183.

- Pikal MJ, Rigsbee DR, Roy ML. Solid state chemistry of proteins: I. Glass transition behavior in freeze dried disaccharide formulations of human growth hormone (hGH). Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2007. 96(10): p. 2765-2776.

- Lam YH, et al. A solid-state NMR study of protein mobility in lyophilized protein-sugar powders. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2002. 91(4): p. 943-951.

- Wang B, et al. The Impact of Thermal Treatment on the Stability of Freeze-Dried Amorphous Pharmaceuticals: II. Aggregation in an IgG1 Fusion Protein. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2010. 99(2): p. 683-700.

- Pikal-Cleland KA, Carpenter JF. Lyophilization-induced protein denaturation in phosphate buffer systems: Monomeric and tetrameric beta-galactosidase. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2001. 90(9): p. 1255-1268.

- Wu C, et al. Advance Understanding of Buffer Behavior during Lyophilization, in Lyophilized Biologics and Vaccines: Modality-Based Approaches, D. Varshney and M. Singh, Editors. 2015. Springer New York: New York, NY. p. 25-41.

- Govindarajan R, et al. Impact of freeze-drying on ionization of sulfonephthalein probe molecules in trehalose-citrate systems. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2006. 95(7): p. 1498-1510.

- Meier BH. Polarization transfer and spin diffusion in solid-state NMR. Advances in magnetic and optical resonance. 1994. 18: p. 1-116.

- Yuan XD, Sperger D, Munson EJ. Investigating Miscibility and Molecular Mobility of Nifedipine-PVP Amorphous Solid Dispersions Using Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2014. 11(1): p. 329-337.

- Mensink MA, et al. Influence of Miscibility of Protein-Sugar Lyophilizates on Their Storage Stability. The AAPS Journal. 2016: p. 1-8.

- Su Y, Andreas L, Griffin RG. Magic Angle Spinning NMR of Proteins: High-Frequency Dynamic Nuclear Polarization and 1H Detection. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2015. 84: p. 465-497.

- Rossini AJ, et al. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization Enhanced NMR Spectroscopy for Pharmaceutical Formulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014. 136 (6), p 2324–2334.

- Ni QZ, et al. In situ characterization of pharmaceutical formulations by dynamic nuclear polarization enhanced MAS NMR. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2017. 121 (34): p. 8132-8141.

- Nie H, et al. Solid-state spectroscopic investigation of molecular interactions between clofazimine and hypromellose phthalate in amorphous solid dispersions. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2016. 13 (11), p. 3964-3975.

Biography

The rest of this content is restricted - login or subscribe free to access

Thank you for visiting our website. To access this content in full you'll need to login. It's completely free to subscribe, and in less than a minute you can continue reading. If you've already subscribed, great - just login.

Why subscribe? Join our growing community of thousands of industry professionals and gain access to:

- bi-monthly issues in print and/or digital format

- case studies, whitepapers, webinars and industry-leading content

- breaking news and features

- our extensive online archive of thousands of articles and years of past issues

- ...And it's all free!

Click here to Subscribe today Login here