Stomach cancer with copies of FGFR2 gene more susceptible to AZD4547

Posted: 27 May 2016 | | No comments yet

Scientists are able to identify patients with stomach cancer who are most likely to respond to AZD4547 by measuring copies of the FGFR2 gene in the bloodstream…

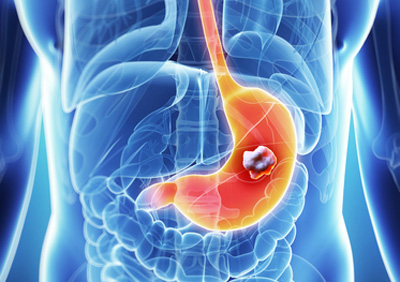

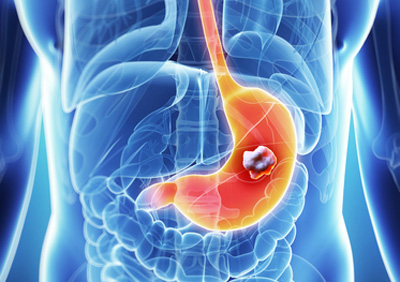

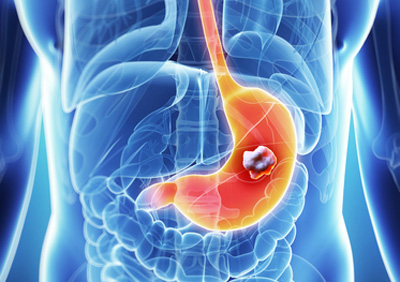

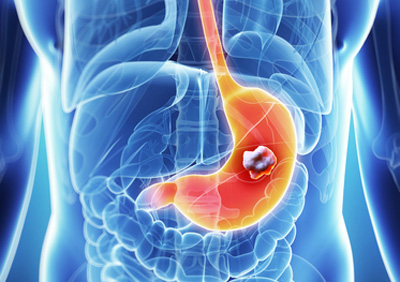

By measuring the number of copies of just one gene from cancer DNA circulating in the bloodstream, scientists have been able to identify patients with stomach cancer who are most likely to respond to treatment with AZD4547.

Stomach cancers with many copies of the FGFR2 gene were found to be particularly susceptible to the experimental drug, an FGFR inhibitor, because the tumours had become reliant on, or ‘addicted’ to, the gene in order to grow.

The new test could be used in future to direct treatment, by identifying a subset of patients who could benefit from an FGFR2 inhibitor.

Assessing the potency of AZD4547

A team at The Institute of Cancer Research, London (ICR) and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust assessed the potency of the FGFR inhibitor AZD4547 in patients with stomach and breast cancer in a phase II clinical trial that screened 341 patients. Initially using tumour biopsies, researchers found many copies of the FGFR2 gene in 9% of cancers among the 135 stomach cancer patients on the trial. Tumours with multiple copies of the gene FGFR2 responded well to the treatment, with three out of nine patients having a response to treatment, and in those patients the drug worked for an average of 6.6 months.

Some 18% of breast cancers were found to have multiple copies of a sister gene, known as FGFR1, and not FGFR2 – but tumours with multiple FGFR1 genes did not have the same susceptibility to the drug.

Interrogating the reason for their observations, the researchers took samples back to the laboratory to pick apart the reasons why the drug worked well in FGFR2 tumours and not in other FGFR genes. They found that FGFR2 hijacks molecular pathways that help cancer grow and spread, and some stomach tumours become addicted to high levels of the gene’s protein product. This phenomenon is known as cancer gene ‘addiction’, and is a weakness that can be exploited by modern targeted therapies.

Shedding light on how tumours can become addicted to genes

Commenting on the findings of his team, Dr Nicholas Turner of The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust said: “Our study has identified a potential new treatment for a subset of patients with gastric cancer, and has explained why some gastric cancers were responding to treatment while others did not. We were able to design a blood test to screen for patients who were most likely to benefit from an FGFR2 inhibitor, helping us to target drug therapy at those patients who were most likely to benefit.

“The research helps shed light on how tumours can become addicted to certain cancer genes, and shows how we can treat the disease effectively by taking advantage of these weak points in cancer’s armoury.”

Professor Paul Workman, Chief Executive of The Institute of Cancer Research, London, added: “This is an important study, which shows how new targeted treatments can exploit cancer’s genetic addictions, and acts as a proof of principle that cancer DNA detected in the bloodstream can be used to guide treatment.”

Related organisations

The Institute of Cancer Research, The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust