TLR agonists suppress tumour growth

Posted: 22 September 2017 | Dr Zara Kassam (European Pharmaceutical Review) | No comments yet

TLR agonists injected directly into a tumour suppresses tumour growth throughout the whole body…

Checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy has been shown to be very effective in recurrent and metastatic head and neck cancer but only in a minority of patients. Researchers have now identified a way to double down on immunotherapy’s effectiveness.

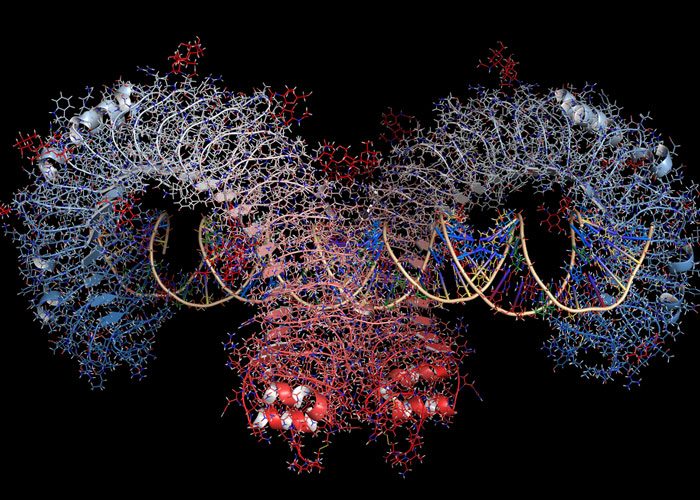

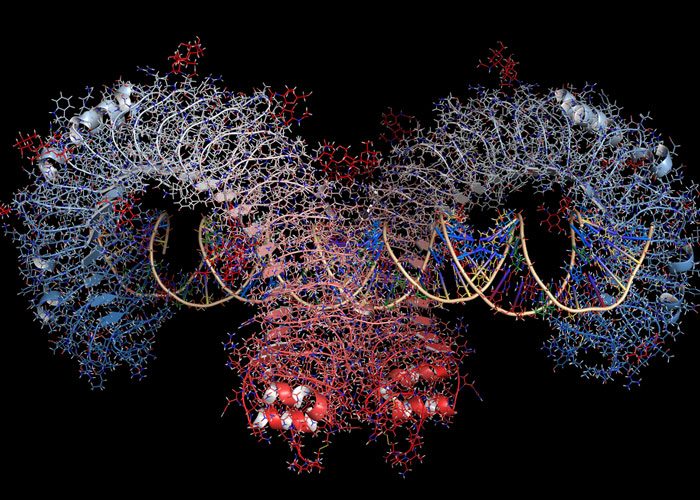

Researchers have reported that a combination of toll-like receptors (TLR) agonists — specialised proteins that initiate an immune response to foreign pathogens or, in this case, cancer cells — and other immunotherapies injected directly into a tumour suppresses tumour growth throughout the whole body.

“The mechanism reverses the phenotype of a tumour by changing its inherent properties to make a tumour more immunogenic,” said Dr Ezra E.W. Cohen, Professor of Medicine at University California San Diego School of Medicine and associate director for translational science at UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center and senior author on the paper.

“In this study, the combination of immunotherapy drugs resulted in the complete elimination of cancer cells and even when re-challenged the tumours did not recur, said Dr Cohen.

Macrophages are specialised immune cells that destroy targeted cells. They are supposed to present antigens to the immune system to get it started, but in cancer, they stop doing that so the immune system is unable to recognise cancer. The combination of drugs restored the ability of macrophages to initiate a tumour response and allow the immune system to eliminate cancer.

To improve the efficiency of checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy on human papillomavirus-negative and HPV-positive head and neck cancers, the team of researchers combined synthetic TLR7 and TLR9 that were developed by Dennis Carson, MD, Professor Emeritus at UC San Diego School of Medicine, with an inhibitor of the protein called programmed death-1 receptor (PD-1) which is responsible for turning off T cells.

TLR agonists cause an innate immune response — that is, the rapid response to a foreign substance in the body. This immediate protection comes at a cost since the nonspecific immune response may harm healthy cells if activation of the immune systems persists. PD-1 inhibitors stimulate an adaptive response calling on B cells and T cells to respond to a specific target, but this process takes longer to go into effect.

In mouse models, the combined TLR agonists and PD-1 inhibitors injected directly into a tumour incited a tumour-specific response by T cells which prevented metastasis or the spread of cancer. When cancer had already spread, the TLR and anti-PD-1 combo eliminated a primary tumour as well as distant tumours. The combination therapy was more effective than either agent alone.

The next step should be to study these drugs in a clinical setting for head and neck cancer using FDA-approved immunotherapy. In addition, Dr Cohen suggests studying these agents with other combinations such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

“As we make a tumour more immunogenic we should be making other therapies more effective and eliminate cancer completely,” said Dr Cohen.

Related topics

Related organisations

t UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center, University California San Diego School of Medicine