The global cannabinoid pharmaceutical industry

Posted: 16 December 2019 | Victoria Rees (European Pharmaceutical Review) | 1 comment

Cannabinoids are of growing interest in the pharmaceutical industry. Mark Tucker explains how this class of compounds is viewed across the world and why regulations surrounding them hinder their progress, yet remain necessary.

Cannabinoids present many opportunities as a therapeutic, with researchers revealing numerous potential uses including the treatment of epilepsy and pain disorders. Despite this, their position in the pharmaceutical industry remains unclear with seemingly contradictory regulations.

European Pharmaceutical Review’s Victoria Rees spoke with Mark Tucker, CEO of TTS Pharma, to discover more about current global regulations surrounding cannabinoids.

Cannabinoids in North America

Tucker explained that in North America, cannabinoids “from a pharmaceutical perspective, are a complete mess.”

He remarked on the confusing status of cannabinoids; despite significant pre-clinical research by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) the active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) are fundamentally still illegal at the federal level, whilst at some state levels have been legalised. According to Tucker, this makes it extremely difficult to hire competent researchers to build a business or development programme around a pharmaceutical pipeline. Also, the prospect of transporting cannabinoids is challenging in the US, as drivers may be able to leave some states but not enter others, hence moving people, products or ingredients across state lines is wrought with problems.

However, Tucker noted that using synthetic materials in R&D pipelines is one way to evade the complications of US regulations, as they are not controlled in the same way.

At the other end of the North American spectrum, said Tucker, is Canada. Having legalised cannabis, the country has been able to forge ahead with developing therapeutic pipelines for cannabinoids relatively freely.

However, Tucker questioned the effect of allowing access to cannabinoids on this liberalised basis. At present, drug-drug interactions with cannabinoids are evident and, along with long-term build-up in adipose tissues, have not been thoroughly studied. Tucker suggests that in five to 10 years, when there is an abundance of data on cannabinoids as a biologically active ingredient , the long-term effects will be revealed.

“If you suddenly lift the curtain and allow free and totally unrestricted access to these compounds without knowing how it interacts or what the impacts are, you could be putting patients at significant risk,” he said.

The size of the US Life Science investment community is substantially greater than in other parts of the world and although there are many opportunities to develop cannabinoids in North America, there is also a range of practical and regulatory complications that could limit the speed of scientific progress in the US.

European regulations

Given that European regulations are more defined and advanced, the opportunity for R&D and clinical teams to gain access to cannabinoid compounds is far easier. Therefore, Tucker says, Europe ought to be an attractive option for US investors seeking to accelerate product development.

The number of well-established and active universities compared to the US and Canada is another reason that investors and research teams may want to choose Europe as a location to develop cannabinoid therapies.

The rest of the world

From a global perspective, Tucker said that there are some countries that view cannabinoids as a big commercial opportunity, such as South Africa, Lesotho and Colombia, attempting to duplicate Canada’s approach.

Conversely, other countries are biding their time and waiting to see how Europe and the US develop their cannabinoid priorities.

Furthermore, some countries do not differentiate between cannabis and the components of cannabis, often due to less sophisticated laws or for cultural reasons.

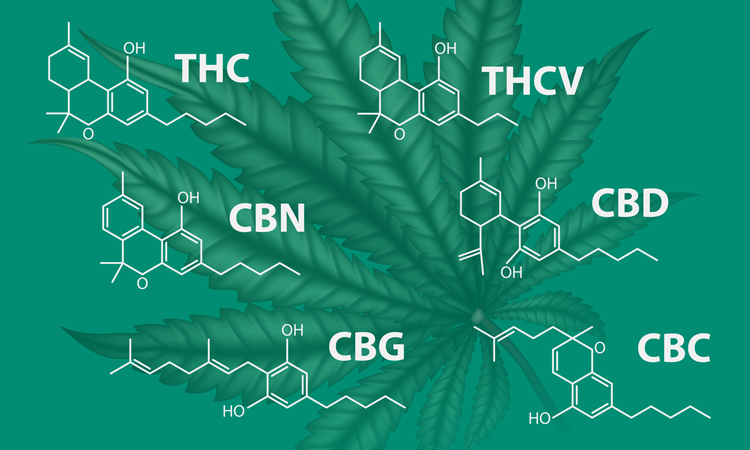

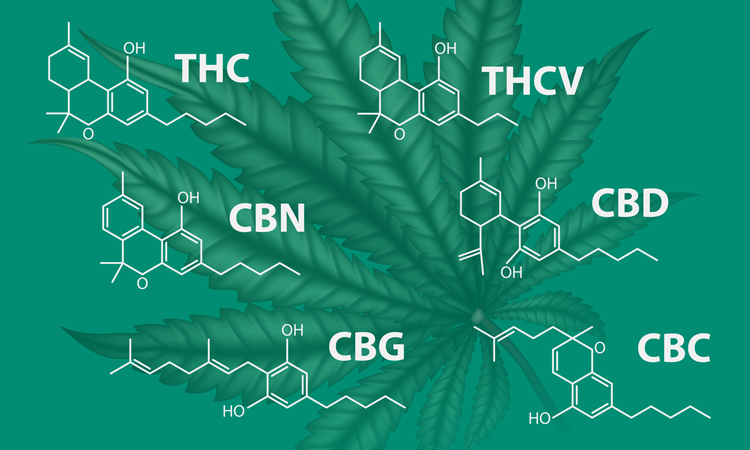

Tucker explained that if a company intends to market a CBD cosmetic or oil free from CBN and THC in countries like the Philippines or Thailand, the law would treat the product in the same way as a medicine containing cannabis, defined as a controlled substance despite the lack of psychoactive ingredients.

This means that in places such as Japan, it is very difficult to get cannabinoids into a clinical programme, due to this “catch-all” definition.

However, Tucker emphasised that ultimately, when trying to develop new pharmaceutical products, centres of excellence are the first port of call for R&D projects. As Europe has some of the best universities in the world, it is the most appealing option for investment in the current regulatory climate.

Medical cannabis versus cannabinoids

For the UK, Tucker made a distinction between ‘medical cannabis’ and ‘pharmaceutical cannabinoids’.

In the UK, medical cannabis is a term that defines an unlicensed product that can be prescribed on a ‘Named Patient Basis’. This “Specials” law allows doctors to prescribe medical cannabis for compassionate or patient-specific reasons that are not accessible via a licensed product elsewhere. Once a product has completed its clinical trials and review, the ability to use this channel to market ceases and the prescribed product is preferred.

Solutions suggested by Tucker to improve patient access and mitigate risks to individual doctors could include extensive education to familiarise them with the benefits and risks they are being asked to prescribe for as well as a separate professional indemnity insurance policy.

Manufacturing and processing

Tucker pointed out that the largest issue from a manufacturing and processing perspective is that companies must be held more accountable than retailers due to their higher position in the supply chain. As the quality and type of cannabinoids must be tightly controlled, there is a legal obligation on the retailer to source from the right supplier if patient safety is to be protected.

Given the many illegal cannabinoid products of questionable quality or origin coming into the UK, Tucker believes that the various competent authorities need more collaboration. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), Food Standards Agency (FSA) and Trading Standards (TS) could all coordinate more effectively, he said. This lack of enforcement is one reason that big pharma are unlikely to become involved in the cannabinoid manufacturing process at this time.

Although investment in R&D pipelines will likely remain high, the same cannot be said for investment in the supply chain which needs serious attention. Tucker believes that there is “huge opportunity” for businesses to become the “next generation” of pharmaceutical companies. However, the right products, technologies and skill sets are required to ensure success in the industry.

Conclusion

Tucker summarised that the clinical and business opportunities presented by cannabinoids are “absolutely enormous.” Despite this, he emphasised that safety should not be compromised and stringent research is still needed to understand the risks and benefits of the ever widening range of cannabinoid APIs.

Therefore, although pre-clinical findings have demonstrated that cannabinoids could make effective medicines, evidence-based research must be undertaken before progress can be made. “Only when this has been completed will we know whether the liberal approaches advocated by so many are the correct way forward or were a premature reaction to unprecedented market forces,” Tucker concluded.

Related topics

Biopharmaceuticals, Cannabinoids, Drug Manufacturing, Drug Markets, Drug Supply Chain, Industry Insight, investment, Manufacturing, Medical Marijuana, QA/QC, Research & Development (R&D), Supply Chain

Related organisations

Food Standards Agency (FSA), Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), Trading Standards (TS), US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), US National Institutes of Health (NIH)

good provide information.