Poliovirus therapy induces immune responses against cancer

Posted: 21 September 2017 | Dr Zara Kassam (European Pharmaceutical Review) | No comments yet

Investigational therapy directly kills tumour cells and unmasks them to the body’s defences.

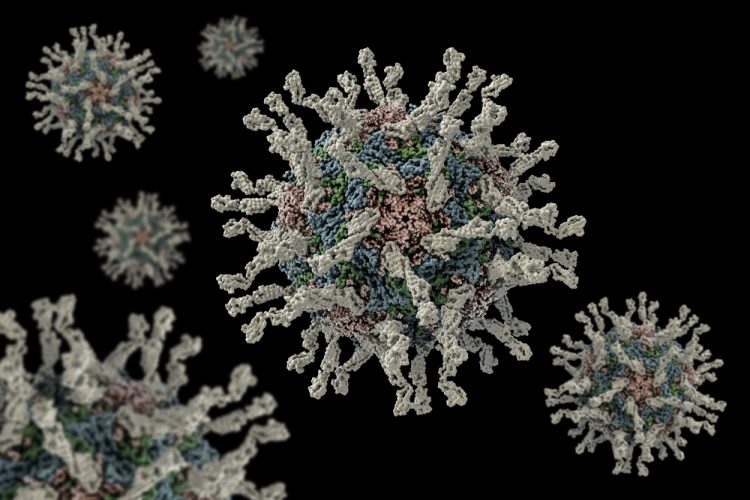

An investigational therapy using modified poliovirus to attack cancer tumours appears to unleash the body’s own capacity to fight malignancies by activating an inflammation process that counter’s the ability of cancer cells to evade the immune system.

Researchers have provided the first published insight into the workings of a therapy that has shown promise in early clinical trials in patients with recurrent glioblastoma, a lethal form of brain cancer.

The modified poliovirus received a breakthrough therapy designation from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) last year, expediting research.

“We have had a general understanding of how the modified poliovirus works, but not the mechanistic details at this level,” said co-senior author Dr Matthias Gromeier, a professor in the Duke Department of Neurosurgery who developed the therapy.

“This is hugely important to us. Knowing the steps that occur to generate an immune response will enable us to rationally decide whether and what other therapies make sense in combination with poliovirus to improve patient survival.”

The research team elucidated how the poliovirus works not only to attack cancer cells directly but also to trigger a longer-lasting immune response that appears to inhibit regrowth of a tumour.

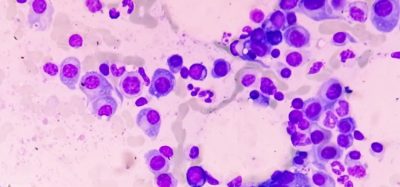

Using human melanoma and breast cancer cell lines, and then validating the findings in mouse models, the researchers found that the modified poliovirus therapy starts by attaching to malignant cells, which have an abundance of CD155 protein.

The CD155 protein is otherwise known as the poliovirus receptor. The modified virus then begins to attack the tumour cells, directly killing many, but not all. This releases tumour antigens.

The second phase of assault is more complicated. By killing the cancer cells, the modified poliovirus triggers an alarm within the immune system, alerting the body’s defences to go on the attack.

This appears to occur when the modified poliovirus infects dendritic cells and macrophages. Dendritic cells then present a tumour to T cells to launch an immune response. Once the immune system is activated against a poliovirus-infected tumour, the cancer cells can no longer hide and they remain vulnerable to ongoing immune attack.

“Not only is poliovirus killing tumour cells, it is also infecting the antigen-presenting cells, which allows them to function in such a way that they can now raise a T-cell response that can recognise and infiltrate a tumour,” said Dr Smita Nair. “This is an encouraging finding because it means the poliovirus stimulates an innate inflammatory response.”

Dr Nair and Dr Gromeier said further studies will focus on the additional immune activity following exposure to the modified virus.

The paper has been published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Related topics

Drug Development, Research & Development (R&D), t-cells, Transition Therapeutics, Viruses

Related organisations

Duke Department of Neurosurgery, Food and Drug Administration (FDA)