MS drug could reduce painful side effects of common cancer treatment

Posted: 30 April 2018 | Dr Zara Kassam (European Pharmaceutical Review) | No comments yet

Researchers have discovered why many multiple myeloma patients experience severe pain when treated with the anticancer drug bortezomib…

Researchers have discovered why many multiple myeloma patients experience severe pain when treated with the anticancer drug bortezomib. The study suggests that a drug already approved to treat multiple sclerosis could mitigate this effect, allowing myeloma patients to successfully complete their treatment and relieving the pain of myeloma survivors.

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is a common, painful side effect of many anticancer drugs that can cause patients to discontinue treatment or because symptoms can persist for years, reduce the quality of life for cancer survivors. “This growing problem is a major unmet clinical need because the increased efficacy of cancer therapy has resulted in nearly 14 million cancer survivors in the United States, many suffering from the long-term side effects of CIPN,” says Daniela Salvemini, Professor of Pharmacology and Physiology at the Saint Louis University School of Medicine.

Bortezomib, which is widely used to treat multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma, causes CIPN in over 40% of patients, but the reasons for this are unclear. Prof Salvemini and colleagues found that bortezomib accelerates the production of a class of molecules called sphingolipids that have previously been linked to neuropathic pain. Rats treated with bortezomib began to accumulate two sphingolipid metabolites, sphingosine 1-phosphate and dihydrosphingosine 1-phosphate, in their spinal cords at the time that they began to show signs of neuropathic pain. Blocking the production of these molecules prevented the animals from developing CIPN in response to bortezomib.

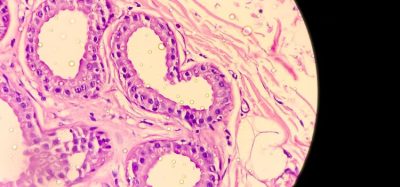

Sphingosine 1-phosphate and dihydrosphingosine 1-phosphate can activate a cell surface receptor protein called S1PR1. Prof Salvemini and colleagues determined that the two metabolites cause CIPN by activating S1PR1 on the surface of specialised nervous system support cells called astrocytes, resulting in neuroinflammation and enhanced release of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate.

Drugs that inhibit S1PR1 also prevented rats from developing CIPN in response to bortezomib. One such inhibitor was fingolimod, an orally administered drug approved to treat multiple sclerosis. Importantly, fingolimod did not inhibit bortezomib’s ability to kill myeloma cells. Indeed, fingolimod itself has been reported to inhibit tumor growth and enhance the effects of bortezomib. “Because fingolimod shows promising anticancer potential and is already FDA approved, we think that our findings in rats can be rapidly translated to the clinic to prevent and treat bortezomib-induced neuropathic pain,” Prof Salvemini says.

The study has been published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Related topics

Drug Development, Drug Targets, Research & Development (R&D)