Who will receive COVID-19 vaccines first?

Posted: 12 October 2020 | Hannah Balfour (European Pharmaceutical Review) | No comments yet

EPR’s Hannah Balfour discusses some of the proposed COVID-19 vaccine distribution plans and how medicinal nationalism and supply deals could prevent “fair and equitable access” to COVID-19 vaccines.

There are currently five investigational COVID-19 vaccines undergoing Phase III clinical trials globally, with several other potential candidates in earlier stages of development. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and the period of frenzied vaccine development it sparked, various international organisations, pharmaceutical companies and vaccine manufacturers have discussed how to fairly distribute vaccines to effectively combat the pandemic.

COVAX and the Fair Allocation Framework

The World Health Organization (WHO), the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and the vaccine alliance Gavi combined forces to create the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator. The vaccine access pillar of the accelerator is the COVAX Facility, which aims to “ensure equitable access to all economies and ensure that income is not a barrier to access”.1 Its aim is to have two billion doses of approved vaccines manufactured by the end of 2021. By joining this facility, any self-financing entity (country) can access COVID-19 vaccines on the same accelerated timeline as the other participants and will be issued vaccine doses based on the WHO’s proposed Fair Allocation Framework.

The WHO allocation strategy suggests doses of vaccines be distributed in two waves:

- At first, each country will be allocated enough doses to vaccinate three percent of their population, followed by proportional allocation of doses until each nation has enough to vaccinate 20 percent of its population against COVID-19

- a subsequent phase to expand coverage of immunisation strategies. Dependent on supply constraints, a weighted allocation approach would be adopted in the follow-up phase; prioritising countries with a greater population of people within the high-risk groups (eg, elderly, healthcare workers and comorbidities like diabetes, asthma etc). This would also consider the country’s COVID-19 vulnerability and threat.2

As of 28 September 2020, a total of 75 countries – including 64 higher-income economies and all 27 EU Member states represented by the European Commission (EC) – had committed to the COVAX Facility.3 A further 86 have submitted non-binding intentions to participate. As a result, almost two-thirds of the global population (approximately 64 percent) are currently committed to or eligible to receive vaccines through COVAX. Within this group, 92 lower-income economies are eligible for financial support through the Gavi COVAX Advance Market Commitment (AMC), a financing instrument aimed at supporting the procurement of vaccines for use in low- and middle-income countries.3

Interestingly, neither the US nor China, two of the world’s largest economies, have agreed to participate in the COVAX project.

In a statement about additional economies joining the COVAX Facility in September 2020, Dr Seth Berkley, Chief Executive Officer of Gavi said: “governments from every continent have chosen to work together, not only to secure vaccines for their own populations, but also to help ensure that vaccines are available to the most vulnerable everywhere. With the commitments we are announcing today [21 September 2020] for the COVAX Facility, as well as the historic partnership we are forging with industry, we now stand a far better chance of ending the acute phase of this pandemic once safe, effective vaccines become available.”

However, in a recent article published in Science4 researchers questioned whether this population-based framework is truly fair, as it “mistakenly assumes that equality requires treating differently situated countries identically rather than equitably responding to their different needs”. To this end, they argue that countries with similar population sizes may face a markedly different level of threat from COVID-19. The authors also stated: “Aid to countries typically is provided in approximate response to the severity of problems. Providing aid merely in proportion to population is unjustified and almost never used. For instance, it would be unethical to allocate antiretrovirals for HIV on the basis of population, rather than on HIV burden. Likewise, a fair distribution of COVID-19 vaccines should respond to the pandemic’s differential severity in different countries.”

Fair Priority Model

In place of the WHO’s Fair Allocation Framework, the authors of the Science paper suggest their own approach to vaccine distribution, indicating distributive justice would be highest in a system that allocates vaccines based on where their power to reduce harm is greatest. They propose their Fair Priority Model as a flexible approach, which prioritises countries based on lessening the most urgent harms first.

According to the authors, there are three dimensions of harm that are key to deciding its significance and urgency: i) are the harms irreversible? ii) how devastating are they? iii) can they be compensated?

Under this model, premature death is the greatest harm as it is irreversible, devastating and cannot be compensated; other direct and indirect health issues, such as stroke and organ damage or increasing unemployment and poverty, are also categorised as devastating and urgent harms requiring mitigation.

The Fair Priority Model has three overarching phases of vaccine distribution but anticipates multiple rounds of vaccine distribution as doses are manufactured. These phases are:

- Reducing premature deaths and other irreversible direct and indirect health impacts. Within phase one, vaccine allocation is based on Standard Expected Years of Life Lost (SEYLL) averted per dose of vaccine. SEYLL is a measure of premature death that calculates life years lost based on a life expectancy table.

- Continuing to use SEYLL as a measurement, phase two seeks to address enduring health harms and begins to correct serious economic and social deprivations (eg, education deficits, unemployment and poverty). This period would include the reversal of school and non-essential business closures.

- Restoring pre-pandemic freedoms by reducing community transmission. In phase three, countries with higher transmission rates are initially prioritised until enough of each population is vaccinated to halt transmission. The authors suggest this will require approximately 60 to 70 percent of the population be immune.

The writers added: “Implementing each phase of the model requires determining the number of vaccine doses each country should receive and the order of receipt. The countries will then allocate vaccine internally to individuals”.

Vaccine nationalism and profiteering preventing fair distribution

While both protocols discussed may seek to ensure all countries have equitable access to vaccines, one potential roadblock to either system is a phenomenon dubbed ‘vaccine nationalism’. This refers to when governments retain doses of vaccines developed and/or manufactured within their borders in order to prioritise supplying their own citizens with a vaccine over foreign parties. With vaccine production traditionally dominated by wealthy economies, such as the UK, US and EU States, the rest of the world would have to be provided for by a majority of smaller outfits, many of which are unable to produce the billions of doses that would be required to meet the needs of the pandemic.

Additionally, the complexity of the leading COVID-19 vaccines – some of which are based on emerging technologies that have never been licensed before – means that even experienced regulatory bodies may struggle to achieve timely approvals. Therefore, production of these vaccines would be limited to a handful of richer nations who are able to approve and effectively scale up production. If vaccine nationalism occurs, developing nations will have extremely restricted access to these products.

While national partiality may be defendable to a certain extent, according to the creators of the Fair Priority Model, retaining additional doses has only a marginal benefit once the rate of transmission in a country drops below one. At this point, the potential benefits to countries whose rate of transmission is greater than one is such that retaining vaccine doses is unjustified.

To highlight the issues with vaccine nationalism, Oxfam analysed data collected by Airfinity and found wealthy nations have now secured more than half of the expected supply of the five most advanced COVID-19 vaccine candidates. It emphasised that these nations represent only 13 percent of the total global population.

The agency warned that the deals struck between vaccine producers, pharmaceutical corporations and these nations (including the UK, EU States, US, Canada, Japan and Australia) mean that even if all five vaccines are successful in clinical trials, 61 percent of the world’s population will not have access to a COVID-19 vaccine until at least 2022. Realistically, it said, the likelihood is that at least one of these vaccine candidates fail in Phase III testing, leaving an even greater proportion of the population without access to a vaccine.

Oxfam added that profiteering and the application of patents is also likely to restrict lower income countries’ access to an effective vaccine.5 This sentiment has also been supported by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, which stated that pricing structures would be one of the biggest barriers to COVID-19 vaccine supply in disadvantaged populations.6

In its explanation of this issue, Oxfam cites the case of Moderna, which has received $2.48 billion in committed taxpayer’s money and has now stated it intends to make a profit from its leading COVID-19 vaccine candidate. According to Oxfam, the pharmaceutical company has sold the options for its total supply to wealthy nations at prices that are out of reach for poorer populations. While this may be an attempt to scale up supply, Oxfam explained that reports indicate the company only has the capacity in place to produce enough for 475 million people (six percent of the global population).

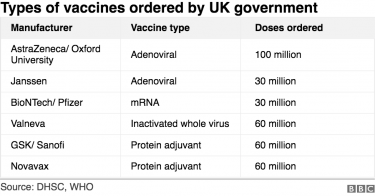

Oxfam added that the deals reveal stark inequalities between countries; where the UK government has obtained deals on several leading vaccine candidates, equivalent to five doses per head of population, Bangladesh has only secured one dose for every nine people.

The organisation does credit some pharmaceutical companies for their willingness to supply for poorer nations: “while Moderna has so far pledged doses of its vaccine exclusively to rich countries, AstraZeneca has pledged two-thirds (66 percent) of doses to developing countries”. However, Oxfam says this will be insufficient, since despite efforts to expand production capabilities, AstraZeneca could still supply a maximum of 38 percent of the global population, a figure which is halved if it is discovered that the vaccine requires two doses for efficacy.

Conclusion

So, who should receive the vaccine first? The answer is an ethical nightmare, but regardless of whether vaccines are distributed based on population or power to reduce harm, the consensus is that all countries – regardless of income – should have vaccine doses allocated to them at the same time. Which individuals countries distribute the doses to once they are received is likely to be those at the greatest risk from COVID-19, such as the elderly, healthcare workers and those with existing comorbidities.

However, with the demand and supply constraints driving profiteering and vaccine nationalism, it is likely that richer nations will have greater access to vaccine doses and therefore receive them first.

References

- COVAX Facility Explainer [Internet]. Gavi. 2020. [Accessed: 28 September 2020]. Available at: https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/covid/covax/COVAX_Facility_Explainer.pdf

- Fair allocation mechanism for COVID-19 vaccines through the COVAX Facility [Internet]. World Health Organization (WHO). September 2020. [Accessed: 28 September 2020]. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/fair-allocation-mechanism-for-covid-19-vaccines-through-the-covax-facility

- List of economies signed up to COVAX Facility [Internet]. Gavi. 2020. [Accessed: 28 September 2020]. Available at: https://www.gavi.org/sites/default/files/covid/pr/COVAX_CA_COIP_List_COVAX_PR_28-09.pdf

- Emanuel, E., Persad, G., Kern, A. et al. An ethical framework for global vaccine allocation [Internet]. Science. September 2020 [Accessed: 18 September 2020]. Available at: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/369/6509/1309

- Gneiting, U., Lusiani, N. and Tamir, I. Power, Profits and the Pandemic: From corporate extraction for the few to an economy that works for all [Internet]. Oxfam. September 2020. [Accessed: 29 September 2020]. Available at: https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/handle/10546/621044

- Fair and equitable access to COVID-19 treatments and vaccines [Internet]. Nuffield Council on Bioethics. May 2020. [Accessed: 29 September 2020]. Available at: https://www.nuffieldbioethics.org/assets/pdfs/Fair-and-equitable-access-to-COVID-19-treatments-and-vaccines.pdf

Related topics

Biologics, Distribution & Logistics, Drug Manufacturing, Drug Supply Chain, Industry Insight, Vaccines, Viruses

Related organisations

AstraZeneca, Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), COVAX, GAVI-the Vaccine Alliance, Moderna Therapeutics, Nuffield Council on Bioethics, Oxfam, The European Commission (EC), World Health Organization (WHO)