Pharma within planetary boundaries

Posted: 21 April 2023 | Dorothea Baltruks (CPHP) | No comments yet

Regulatory changes along a drug’s lifecycle should ensure that the health benefits of pharmaceuticals, which have a large ecological footprint, do not cost the environment. Dorothea Baltruks, Research Associate at the Centre for Planetary Health Policy, outlines how forthcoming EU pharmaceutical legislation could pave the way to solutions.

We have 27 years left to transform the EU into a climate-neutral continent in order to keep the ecological catastrophes that the climate crisis brings at a manageable level – to find solutions for every flight taken, every car driven and every medical treatment undergone in the EU. Other sectors are already on the way to reducing their emissions and have received much public and political attention. Yet the pharmaceutical sector is just starting that journey; one that will be impacted substantially by consequences of the climate crisis – from heatwaves to new infectious diseases, to longer hay fever seasons and new allergies.1

Pharma’s climate footprint

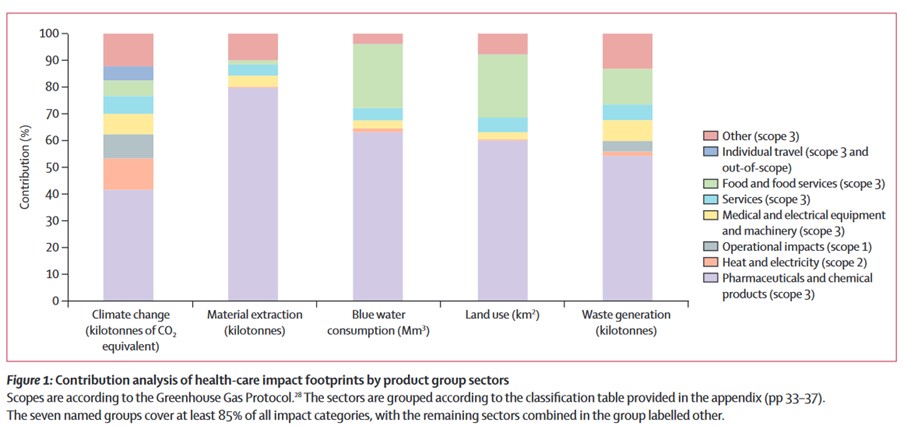

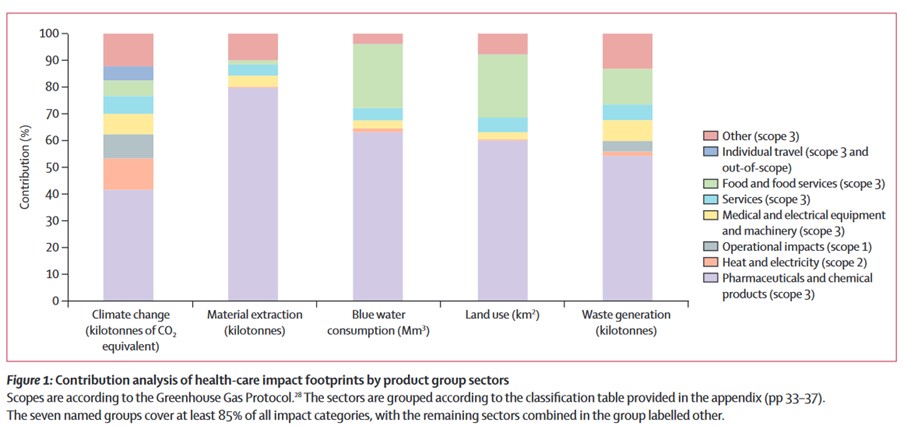

Numbers first: the health system produces 4.7 percent of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions – more than twice as much as aviation. Seventy five percent of EU health systems’ emissions are released indirectly along the supply chain of pharmaceuticals, medical and other products.2 A study found that pharmaceuticals and other chemical products are responsible for 40 percent of the Dutch healthcare system’s greenhouse gas emissions and about 80 percent of its share of material extraction.3

Credit: Steenmeijer M, et al. The environmental impact of the Dutch healthcare sector beyond climate change: an input-output analysis. Lancet Planetary Health. 2022; 6: 949-57.

Hence, every country that looks at decarbonising its health sector – and all EU Member States must – will quickly look at the pharmaceutical industry. In addition, the number of active substances detected in the environment has been increasing with unknown consequences for ecosystems and the accumulation of substances in food chains.4

Together with a legal expert from the Bucerius Law School Hamburg, we looked at the legal and political frameworks that could enable the German pharmaceutical sector to become more sustainable.5 We considered the whole lifecycle of a drug, as environmental impacts arise at every stage of the process from development and production to administration and disposal.

Giving environmental risk assessments teeth

Since 2005, the authorisation of a human pharmaceutical product requires an environmental risk assessment (ERA). The problem is that if potentially undesirable effects on the environment are identified, this remains largely inconsequential for the authorisation. Interestingly, this is not the case for veterinary medicines, where the authorisation can actually be refused if the risk is not adequately mitigated. The ERA therefore needs teeth – which does not mean it should be a barrier to the authorisation of new medicines – but it should require pharmaceutical companies to minimise harmful effects on the environment, which indirectly also harm our health.

the ERA… has provided data on the environmental impacts of pharmaceuticals; data that is often missing for drugs that were authorised before [its] introduction”

However, the ERA is not completely worthless. Rather, it has provided data on the environmental impacts of pharmaceuticals; data that is often missing for drugs that were authorised before the introduction of ERA. Therefore, another question is how we can obtain reliable, transparent information on older drugs. There is still a huge gap in publicly available data for most drugs sold in the EU, which is the first barrier to assessing the status quo.

The leaked draft of the European pharmaceutical package is promising on this point as it states that marketing authorisation may be refused if the ERA is not completed or risk mitigation measures are insufficient, and that an ERA programme should be set up for medicines that were authorised before the introduction of the ERA.6

Scrutinising the supply chain

An important but often opaque consideration is the supply chains in non-EU countries, which play a predominant role especially in the production of generic drugs and antibiotics. Germany’s new Act on Corporate Due Diligence Obligations in Supply Chains (LkSG) is a first step to holding companies to account for human rights violations and soil, water and air pollution. It does not include impacts of the climate and biodiversity crises, though, and only applies to a company’s own operations and direct suppliers.

The European Commission’s draft Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive would go further and actually require large companies to bring their strategies in line with the 1.5°C-limit and be applied to the whole supply chain.7 We would also argue that the pharmaceutical sector should be identified as a “high-impact” sector, given its significant ecological impact.

The obvious question is: if the EU introduces stricter regulations for pharmaceuticals, won’t manufacturers be further deterred from producing medicines in the EU?

In terms of medicines sold in the EU, that should not be a major concern as the continent will remain a major market for pharmaceutical companies, even if the regulatory requirements are strengthened. For the production of pharmaceuticals sold elsewhere in the world, this may be true to a degree, although newer drugs with high margins and promising potential will still be developed in the EU, given the rich research and development environment here.

Other countries are looking at environmental impacts, too. The National Health Service in England has set out a clear roadmap towards climate neutrality including reporting emission reduction obligations for its suppliers. Pharmaceutical companies know that they must address their ecological impact and some have already set out ambitious plans and targets to play their part.

Information, education, efficacy

Ecological aspects should also be integrated into the training and further education of other healthcare professionals – such as pharmacists – so that they can competently advise customers. Advising on more environmentally-friendly alternatives to most medicines is difficult, given that the required information is often missing. The Stockholm region in Sweden attempted this by developing a “Wise List” of medicines between 2017 and 2021, which enables physicians to select the least environmentally harmful product from those with equivalent efficacy.8

“Prominent examples of climate-unfriendly medicinal products are…anaesthetic gases like desflurane…and metered dose inhalers”

The most prominent examples of climate-unfriendly medicinal products are the focus of medical associations trying to reduce their use: anaesthetic gases like desflurane (a 2,500 times more potent greenhouse gas than CO2, which is already being phased out in England)9 and metered dose inhalers, which the German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians advises be replaced where possible with more climate-friendly dry powder inhalers.10

Is the journey towards a pharmaceutical sector that operates within the planetary boundaries going to be easy? Of course not. The required actions will be complicated, maybe even controversial. But so is the required transformational process in every sector. Let’s remember: the status quo or too little action will lead us into multiple ecological catastrophes that are a much greater threat to our economies, health and societies than any legislative change proposed in our policy brief could ever be.

About the author

Dorothea Baltruks is a Research Associate at the Centre for Planetary Health Policy (CPHP) where she focuses on the transformation of the German health system towards climate resilience and sustainability. After studying international and social policy at King’s College London and the London School of Economics and Political Science, Dorothea worked for a health consultancy in the UK and the European Social Network. Later, she led the research policy, global and data analysis portfolios at the Council of Deans of Health, which represents the UK universities’ health faculties. Before joining CPHP, she advised the Green Party’s health spokesperson in the Bavarian state parliament.

References

- van Daalen K, et al. 2022. The 2022 Europe report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Towards a climate resilient future. The Lancet Public Health. 7(11): 942-965.

- Health care without harm. Health care’s climate footprint – how the health sector contributes to the global climate crisis and opportunities for action. [Internet] Health care without harm climate-smart health care series green paper number one. 2019. [cited 23Apr]. Available from: https://noharm-global.org/sites/default/files/documents-files/5961/HealthCaresClimateFootprint_092319.pdf.

- Steenmeijer M, et al. The environmental impact of the Dutch health-care sector beyond climate change: an input-output analysis. Lancet Planetary Health. 2022; 6: 949-57.

- Gildemeister D, et al. Improving environmental protection in EU pharmaceutical legislation. 2022. Dessau-Roßlau: German Environment Agency.

- Baltruks D, Sowa M, Voss M. Strengthening sustainability in the pharmaceutical sector. [Internet] Berlin: Centre for Planetary Health Policy. 2023. Available from: https://cphp-berlin.de.

- European Commission. European Pharmaceutical Strategy – European Commission (draft) Pharmaceutical package.

- European Commission. 2022. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on corporate due diligence with regard to sustainability and amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937.

- Stockholm Region (n.d.). Information on environmental effects of medicinal products. [Internet] Janusinfo Region Stockholm. [cited 23Apr]. Available from: https://janusinfo.se/beslutsstod/lakemedelochmiljo/pharmaceuticalsandenvironment.4.7b57ecc216251fae47487d9a.html.

- NHS organisations cut desflurane in drive for greener surgery. [Internet] NHS England. [cited 23Apr]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/whats-already-happening/nhs-organisations-cut-desflurane-in-drive-for-greener-surgery/.

- German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM). 2022. Climate-conscious prescription of inhaled medicinal products.

Related topics

Big Pharma, Biopharmaceuticals, Drug Manufacturing, Drug Safety, Drug Supply Chain, Regulation & Legislation, Supply Chain, Sustainability, Therapeutics

Related organisations

Centre for Planetary Health Policy (CPHP), European Commission (EC)