Intravenous delivery of TB vaccine found to dramatically improve potency in models

Posted: 2 January 2020 | Hannah Balfour (European Pharmaceutical Review) | No comments yet

New research has shown that intravenous injection of the BCG vaccine dramatically reduces monkey susceptibility to TB bacteria and lung inflammation.

Research has found that intravenous (IV) injection of the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine provides almost 100 percent protection against Tuberculosis (TB) bacteria and concurrent lung inflammation in monkeys. The findings demonstrate a vast improvement on the protection afforded by regular cutaneous injection of the vaccine.

BCG is a commercially available human TB vaccine made of a live, weakened form of TB bacteria found in cattle. BCG is among the most widely used vaccines in the world, but its efficacy varies widely and contributes to the high death rates associated with TB.

…for individuals with the IV vaccine, there was virtually no TB bacteria in their lungs”

Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), both US, discovered that intravenous TB vaccination is highly protective against infection in rhesus macaques compared to the standard injection directly into the skin, which offers minimal protection.

“The effects are amazing,” said senior author Dr JoAnne Flynn, professor of microbiology and molecular genetics at the Pitt Center for Vaccine Research. “When we compared the lungs of animals given the vaccine intravenously versus the standard route, we saw a 100,000-fold reduction in bacterial burden. Nine out of 10 animals showed no inflammation in their lungs.”

The researchers separated their colony of monkeys into six groups: unvaccinated, standard human injection into skin, stronger dose into skin, mist, injection plus mist and the stronger dose of BCG delivered as a single shot directly into the vein. Six months later, they exposed the animals to TB bacteria and monitored the models for signs of infection.

Monkeys that received the standard human dose all had persistent lung inflammation and the other injected and inhaled vaccines offered similarly modest TB protection.

However, for individuals with the IV vaccine, there was virtually no TB bacteria in their lungs and only one monkey in this group developed lung inflammation.

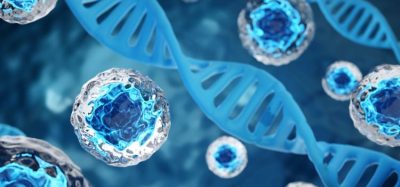

“The reason the IV route is so effective is that the vaccine travels quickly through the bloodstream to the lungs, the lymph nodes and the spleen and it primes the T cells before it gets killed,” said Flynn.

Flynn’s team found BCG and activated T cells in the lungs of all the intravenously vaccinated animals. Among the other groups, BCG was undetectable in the lung tissue and T-cell responses were comparatively weak.

The researchers plan to continue to develop their findings by testing whether lower doses of IV BCG could offer the same level of protection without the side effects, which mostly consist of temporary inflammation in the lungs.

“We’re a long way from realising the translational potential of this work,” Flynn said. “But eventually we do hope to test in humans.”

Research published in Nature.

Related topics

Dosage, Drug Development, Immunisation, t-cells, Therapeutics, Vaccines

Related organisations

Pitt Center for Vaccine Research, The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine