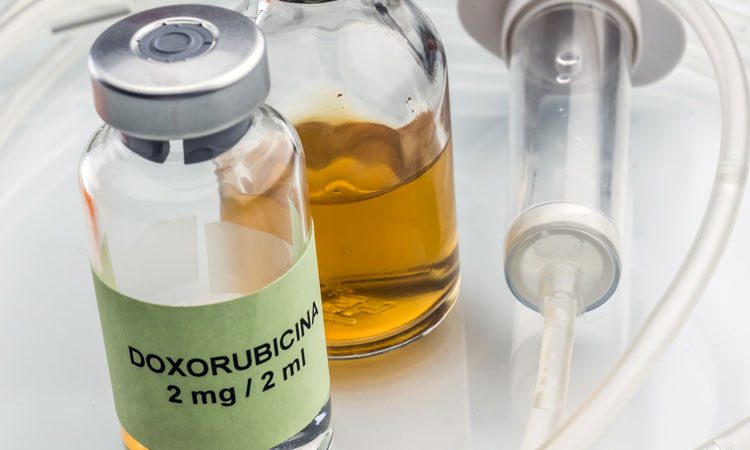

Doxorubicin disrupts the immune system to cause heart toxicity

Posted: 9 August 2018 | European Pharmaceutical Review | No comments yet

Doxorubicin induced irreversible dysregulation which decreased the levels of lipoxygenases and cyclooxygenases in the left ventricle…

A chemotherapy drug widely used in ovarian, thyroid, lung, bladder and stomach cancers may cause heart toxicity.

Doxorubicin caused dose-dependant heart toxicity in mouse models, which could later lead to congestive heart failure.

Researchers at the University of Alabama, Birmingham (UAB), described the disruption of the metabolism controlling the immune responses in the spleen and heart, as an important contributor to the pathology of the heart.

As immune responses are vital to maintain the health of the heart, repair and the control of inflammation, the dysregulated immunometabolism impairs the resolution of inflammation. Chronic, non-resolved inflammation then leads to heart failure.

Professor Ganesh Halade from UAB led the team of researchers using mouse models to study the effect of the commonly used chemotherapy drug on immunometabolism. In mice, doxorubicin induced fibrosis in the heart, increased apoptosis (programmed cell death) and impaired the pumping function of the heart. The drug also caused a wasting syndrome in the heart and spleen.

Immunometabolism is the study of how metabolism regulates immune cell function, and involves two immune-responsive enzymes, cyclooxygenases and lipoxygenases. These enzymes create a variety of bioactive lipid mediators that regulate immune cell responses.

The spleen acts as a reservoir of immune cells that travel to the site of heart injury to begin clearing damaged tissue, thus playing a role initiating the immune response after a heart attack. Prof Halade and the research team discovered that doxorubicin has a deleterious response to the spleen.

The team found that the drug induced irreversible dysregulation which decreased the levels of lipoxygenases and cyclooxygenases in the left ventricle. In turn, this reduced the bioactive lipid mediator levels that would usually resolve inflammation.

The drug also ‘poisoned’ a group of marginal zone immune cells, called CD169+, in the spleen. The spleen was found to reduce in size and resulted in the loss of specialised macrophage cells. This impaired the defence system in the mouse models, as the macrophages are usually the first cells to respond to sites of injury or infection.

The researchers also found that the drug caused an imbalance of cell signalling molecules called chemokines and cytokines, suggesting that the defence capacity of the spleen-leukocyte immune cells was restricted. These involved decreased levels of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in the spleen, along with decreased levels of the immune cell marker MRC-1 (also known as CD206) in the heart.

In the non-cancer mouse model, the researchers conclude that doxorubicin has a splenocardiac impact, and knowledge of the mechanisms of the drug can help to preserve the health of the heart and the spleen in cancer patients taking doxorubicin.

The study was published in the American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology.

Related topics

Clinical Development, Drug Development, Drug Safety, Drug toxicology studies, Research & Development (R&D)