Blood test detects early stages of Alzheimer’s disease

Posted: 5 February 2018 | Dr Zara Kassam (European Pharmaceutical Review) | No comments yet

Scientists have developed and validated a blood test for Alzheimer’s disease, with the potential to massively ramp up the pace of Alzheimer’s disease drug trials…

Scientists have teamed up to develop and validate a blood test for Alzheimer’s disease, with the potential to massively ramp up the pace of Alzheimer’s disease drug trials.

The blood test measures a specific peptide in the blood to inform scientists, with 90 percent accuracy, if a patient has the very earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

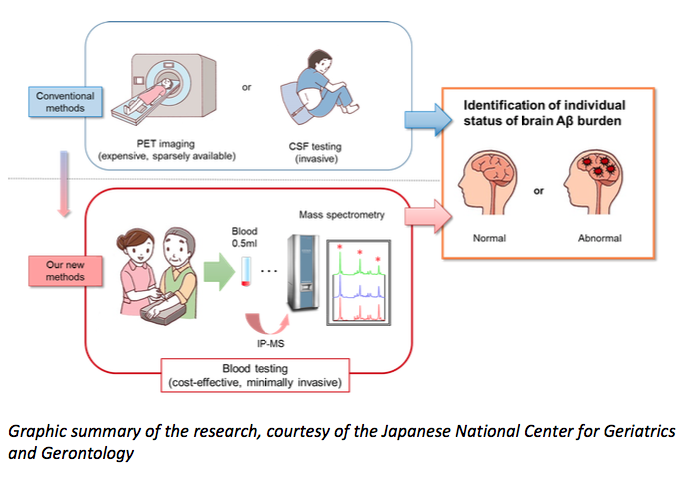

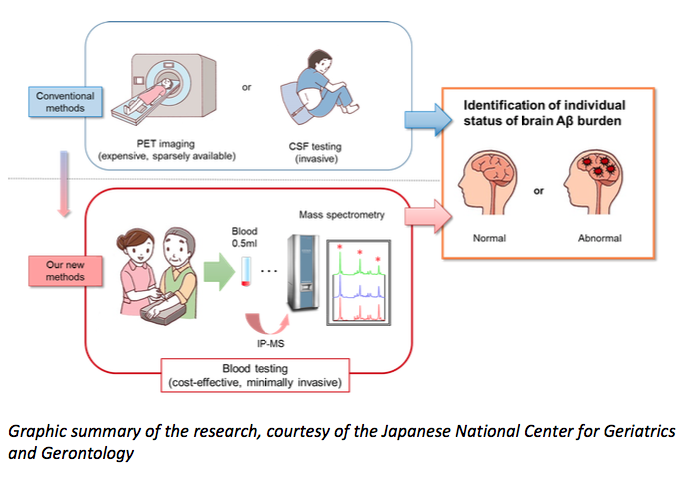

Blood samples from patients in a large study from the Japanese National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (NCGG) were initially analysed to identify the relevant peptides. Those indicating brain beta-amyloid burden were then tested against patient samples from the Australian Imaging, Biomarker and Lifestyle Study of Aging (AIBL), to validate the results.

Until now, the only way to identify amyloid-β in the brain — short of an autopsy — has been to image the brain using positron-emission tomography, or to measure levels of the protein directly in cerebrospinal fluid from the spinal cord. Both of these procedures have been used to help recruit patients into recent trials, but the tests are expensive and uncomfortable.

Professor Katsuhiko Yanagisawa, Director-general of Research Institute at NCGG, says: “Our study demonstrates the high accuracy, reliability and reproducibility of this blood test, as it was successfully validated in two independent large datasets from Japan and Australia.”

To measure the levels of several amyloid-β fragments in blood samples, as well as a fragment of a larger protein from which amyloid-β derives, Prof Yanagisawa and his colleagues combined two existing techniques — immunoprecipitation and mass spectroscopy. Their results matched those achieved through brain imaging and the analysis of spinal-cord fluid in two separate cohorts involving 121 people in Japan and 252 people in Australia. Each cohort included individuals aged between 60 and 90. Some of the participants were healthy; some showed mild impairment in their cognitive skills, and some had Alzheimer’s disease.

Graphic-summary-of-new-Alzheimers-blood-test (The Florey Institute of Neuroscience & Mental Health)

The authors say that larger and more long-term studies are needed to confirm how accurate the blood test is at identifying high levels of amyloid-β in human brains. If it is highly accurate, then the test could help recruitment for clinical trials, because it is relatively easy and cheap to do.

Dr Koichi Tanaka at Shimadzu Corporation was instrumental in developing the initial blood testing procedure. Professor Tanaka won the Nobel prize in Chemistry in 2002 for the technique. “From a tiny blood sample, our method can measure several amyloid-related proteins, even though their concentration is extremely low. We found that the ratio of these proteins was an accurate surrogate for brain amyloid burden.”

One of the essential hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease is a buildup of the abnormal peptide in the brain, called beta-amyloid. The process starts silently about 30 years before outward signs of dementia, like memory loss or cognitive decline, have begun.

Current tests for beta-amyloid include brain scans with costly radioactive tracers, or analysing spinal fluid taken via a lumbar puncture. These are expensive and invasive, and generally only available in a research setting. A diagnosis is usually made without these tools, by assessing a patient’s range of symptoms.

Laureate Professor Colin Masters of the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health, and The University of Melbourne has been at the forefront of Alzheimer’s research since the 1980s.“This new test has the potential to eventually disrupt the expensive and invasive scanning and spinal fluid technologies. In the first instance, however, it will be an invaluable tool in increasing the speed of screening potential patients for new drug trials.”

“Progress in developing new therapeutic strategies for Alzheimer’s disease has been disappointingly slow. None of the three drugs currently on the market treat the underlying disease. New drugs are urgently required, and the only way to do that is to speed up the whole process. That requires trials with rigorous and economical patient selection, to avoid recruiting patients who may not even have Alzheimer’s disease. Due to the long timespans involved, pharmaceutical companies require accurate predictions of who is most at risk.”

The breakthrough was the result of an extensive international collaboration between industry and academia in both Japan and Australia. The key technology, known as IP-MS, was implemented by Shimadzu Corporation in Japan. The University of Tokyo, Kyoto University, Kindai University, and Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology all contributed to the work. In Australia, the AIBL study upon which the test was validated, is a partnership between the Florey Institute, The University of Melbourne, CSIRO, Edith Cowan University, and Austin Health.

The research is available to view on the Nature website.

Related topics

Analytical techniques, Biomarkers, Clinical Development, Clinical Trials, Imaging, Mass Spectrometry, Spectroscopy

Related organisations

Australian Imaging Biomarker and Lifestyle Study of Aging (AIBL), Kindai University, Kyoto University, Shimadzu Corporation, The University of Melbourne, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology, University of Tokyo

Related people

Dr Koichi Tanaka, Professor Colin Masters, Professor Katsuhiko Yanagisawa